Malternatives Part 1: Rum 101

A Whisky Lover’s Overview

In Case Of Whisky Fatigue, Break Fill Glass.

Another Ainsley feature not dedicated to whisky. I’d forgive you for thinking that I actually don’t like whisky that much and I am in reality trying to undermine this website by alienating its core followers, but you’d be wrong. Thankfully.

After the positive reception of my non-whisky “Whisky and Wine 101” guide, this piece was an inevitability. However, it was originally inspired by one of Earie’s reviews from a while back, as well as blog posts from Maltymission.

Whisky fatigue is a thing and it can affect all of us. I suffer from it from time to time and when these periods occur I dread opening one of my prized bottles for fear of not enjoying it to the fullest. I think whisky fatigue can especially occur if you’re honed in on your favourite style of whisky and seldom step out of your comfort zone, like someone only drinking sherry bombs for example. Nothing wrong in knowing your preferences, but I believe a little variety can help keep the boredom away.

Sometimes though, switching to a different style of whisky won’t be enough. An entirely different drink is needed, to open up the field of perspectives, and re-engage the flavour-seeking machine inside all of us. My spirit of choice is definitely malt whisky, especially those hailing from Caledonia, but I must admit that I enjoy other spirits from time to time; some more than others. My job has allowed me to experience a vast range of distillates from the world over, and I have made true discoveries along the way which I hope to share with you here.

This feature series will first and foremost be about the malternatives I personally enjoy and the approach will be from the angle of a whisky enthusiast. For example, I won’t talk to you about vodka, which is often just diluted neutral grain spirit, or craft gin, of which there are tons of good ones, but these I personally tend to enjoy in a cocktail rather than neat. I won’t talk about agave based spirits and their siblings, like raicilla, sotol, or more famously, mezcal and tequila because, though I recognise that there are high quality bottlings, I don’t particularly enjoy them. In this case that is a personal thing though, and I suspect that many ‘peat freaks’ here would enjoy quality mezcal very much.

I won’t mention whiskies made from other grains than malt either, simply because I still consider those as whisky, and as such, not different enough for me to qualify as a malternative - despite the term. Again, this is only my personal view of things and if you only ever drink rye whisky, a peater from Islay will surely be a change of pace.

Another reason for doing that, is that if I start to review bourbon, Ogilvie - hailing from the whisky desert - won’t have anything more to write about.

I’ll divide this into a few chapters and punctuate each with a few reviews of bottles I own. Keep in mind I buy much less malternatives than whisky, so I tend to gravitate towards higher end stuff. What’s the point of owning only one bottle of Armagnac if it is just average?

So without further ado, strap in for a dive into the wonderful world of spirits distilled from basically anything but grain.

Let’s begin with cane.

The subject of cane spirits is vast, which means trying to summarise it in a few pages is both a daunting task and a futile effort. Yet, I’ll summon the masochist in me and get to it.

Rum, Ron, Rhum. A Quick Cheat-sheet.

So, what the hell is Rum?

Rum is a spirit now produced the world over, and made from sugarcane juice or its derivatives. Now, for those of you who already know a little bit (or a big bit) about it, please do not throw rocks at me as I broadly simplify all of this. Thankfully we don’t pay the website host by the word, but my goal isn’t to write a book here either.

Most Rum is produced using molasses, which is, to put it simply, leftovers of the sugar refinement process. It’s actually heavily reduced cane juice that ends up resembling a thick black paste and still contains some sugar. Molasses are typically diluted and fermented, before being distilled in either a column or pot still. It can then be aged or not, and bottled. Rum distilled from molasses can exhibit a wide range of flavours, but it tends to be round, caramel-y, and mouth coating.

cut sugar cane

There is still a small proportion of rum made from pure, fresh cane juice, championed by my fellow countrymen and women in the French Caribbean and at La Réunion; but it is also produced in Haïti, Brazil and Madeira for example. Again, depending on the production methods used, it can vary wildly, but in general it tends to be dryer and grassier than molasses-based rum. While molasses-based rum can be produced the world over, as molasses is shelf stable, pure cane juice rum can only be made where sugarcanes are grown, as the quality of the juice decreases very rapidly after harvest.

There are many countries producing rum, and as such I cannot give you a detailed overview of each and everyone of them. As such, I’ll focus on the ones making - in my humble opinion - rums of the best quality. After all, the majority of our readers are educated tasters who like your whisky flavourful and presented in a transparent way, so I’ll assume you’ll want rums and other spirits done in a similar manner whilst browsing for malternatives.

Rum regulations do exist, but some are not recognised by other countries and they differ massively from one place to the next, notably on the subject of ageing in casks. While some countries allow the production of unaged rum, some, like Cuba and Guyana, impose a minimum ageing period which means that white rums there are actually charcoal filtered. Furthermore, a dark rum isn’t necessarily aged, it could be white, unaged rum spiked with things such as e150, caramel, sugar syrup, molasses or spices and artificial aromas. To sum it all up, “white” and “dark” rum don’t necessarily mean anything when it comes to ageing.

A slightly outdated but still relatively effective way of classifying rums is by their “tradition”, of which there are a few. However, we can narrow it down to three, named after the former colonial power who was ruling this part of the world. As you may well know, rum’s reputation, more than any other spirit, was built on the back of slaves working on plantations in colonies of the Caribbean:

British tradition rums: They are made from molasses, and distilled either in columns or pot stills. Pot still rums are usually - but not always - the best. They are almost always aged, at least a few years, up to decades. Examples of countries producing British style rums are Barbados, Jamaica, Antigua & Barbuda, Saint Lucia, Guyana or Trinidad-and-Tobago. I suspect this is where most of the malt enthusiasts will find excitement in rum.

Spanish tradition rons: Also made from molasses, although some producers here and there have switched partially or totally to cane syrup (reduced cane juice). They are almost always column distilled and usually bottled with additives such as sugar. It is usually the cheapest kind of rum, both in price and quality. There are some exceptions here and there, but there is a general consensus that Spanish-style rons are never as complex as British or French-style rums.

French tradition rhums: Although French overseas regions such as Martinique or la Réunion produce a substantial quantity of molasses rum, what is implied by the term French-tradition is cane juice based rum. It can be called Rhum Agricole in Martinique, Guadeloupe, Madeira (though not French style here obviously) and La Réunion, but cane juice rhum made in Haïti for example cannot use the term, which is protected by European law. Pure cane juice rums are more often than not distilled in a column, and are highly regarded amongst rum maniacs, as they’re very often bottled without any additives and made according to a stricter standard.

molasses

By the way, if you were wondering why I use three different spellings for rum, it just depends on the country of origin’s language. Nobody will hate you for using only one, except maybe some snobby French producers. Don’t mind them.

Now let’s dive more into the specifics of a few notable producing countries and islands:

Jamaica

The George Clinton of rum (British tradition)

Jamaica is the country that made me like rum in the first place. I do think it is a great place to start for a whisky enthusiast, as the rums produced here tend to be very full bodied and bursting with flavour, even when originating from a column. This is due to long fermentation times, which has always been the custom over there. This produces rums which are commonly called “high ester”. As many of you will already know, esters are a type of congener, and are flavour molecules.

To put it simply, the longer the fermentation, the more esters you get, and the more esters you have, the more flavourful and powerful your rum is going to be. Calm down rum geeks, I said “to put it simply”. It is also common practice to spike the fermenting molasses with what they call dunder, which is simply the residue left in the pot after a distillation run, or what a Scotsman might call pot ale. The highly acidic content of dunder helps to create more congeners during fermentation.

There is also the subject of muck, which must be addressed.

It is rumoured that all distilleries in Jamaica have “muck pits” where they throw away spent cane fibres, fruits and even goat heads to rot and then put some of that in the fermentation tanks. First of all, the only two distilleries in Jamaica that, to my knowledge, actually have a muck pit are Long Pond and Hampden; and secondly, the animal carcass claims seem to be fantasy. But the pit at Hampden might help to explain why it certainly is the most intense rum produced in the country.

Appleton estate, Jamaica

Pot distilled Jamaican rums are amongst the most complex rums that exist, and their intensity has enamoured lots of whisky drinkers along the years. I say pot distilled, but in reality I should rather say double retort pot distilled. You see, Jamaican producers, as many rum producers in former British colonies such as Barbados and Guyana, have found a way to produce a pot still rum in only one distillation run. The swan neck of the pot still goes to a retort, which is a tank half filled with either water or feints from previous runs, and then a second one, which effectively raises the alcohol content at the end of the distillation run to around 75-80%, compared to merely 20-30% from regular pot distillation (such as in Scotch whisky for example). A retort is basically the same thing as a doubler or thumper in American whiskey production. This helps massively with efficiency.

Pretty much all distilleries in Jamaica also produce rums of different ester content, from light to heavy. This practice dates back to the time when the rums produced there were destined to be blended, sometimes only in small proportions to flavour rectified spirit or kitchen preparations. These different distillates are called marques/marks, and are specific to each and every distillery. It is also worth noting that Jamaican regulations prohibit the sweetening of rum, which is always good news.

Jamaica is one of the most renowned rum producing countries, yet it only has 6 distilleries in operation:

Clarendon: Also called Monymusk, and it’s the second biggest distillery in the country. They produce a very wide range of rums, both from columns and double retort stills. Clarendon rums tend to be a good introduction to Jamaican rum, and are widely available amongst indies. They exhibit the classic Jamaican aromas of very ripe exotic fruits, as well as a tiny bit of “dirtiness”, with olive brine or burning rubber for example. The heaviest pot still mark they make goes up to around 600g of esters per hLAA (Hectolitre of absolute alcohol) , which is quite flavourful, but not as heavy as some other distilleries. The distillery sports a very modern four-column still which essentially allows them to produce neutral alcohol if they ever need to. The rums you’ll find amongst indies will be more flavourful though.

Long Pond: Owned by the same company - National rums of Jamaica, a joint venture by the Jamaican government, Maison Ferrand and Diamond Distillers Limited. Long Pond only has double retort pot stills, and makes a heavier style of rum. With marques going up to 1600g of ester per hLAA - called TECA, TECB and TECC - it certainly is flavourful. It is also often found amongst indies. Expect oily dirty funkiness, rotting tropical fruits and chemicals. Might be the least approachable Jamaican rum, but delicious nonetheless, especially when you find a good one.

Appleton Estate: One of the distilleries belonging to Campari, it makes a widely distributed rum of the same name. You might have seen it at your local retailer or even supermarket. Appleton rums can be wonderful, but a higher ABV and naturally presented ones are very rare and expensive. The 40% alc. core range is decent - and sugar-free - but not particularly exciting. A good option for a Mai-Tai for sure; just a bit bland on its own in my opinion.

New Yarmouth: New Yarmouth also belongs to Campari and is the home of the Wray & Nephew brand, the most consumed rum in Jamaica. Very rare to find amongst indies and practically impossible to visit. New Yarmouth is famous for the heavy, funky, industrial style of rum that made Wray & Nephew overproof white so popular. Rotting bananas for the win.

Worthy Park: Located in Lluidas Vale, which is also the name you’ll find on some indie bottlings. Worthy Park is independently owned and produces pot still rum that has a very defined exotic and fruity character, with still a tiny bit of the trademark Jamaican funkiness. Very common amongst indies, you’ll find medium bodied to heavy rums, but not as heavy as Long Pond for example.

Hampden: Last but definitely not least, the beast that is Hampden. This producer is celebrated by rum geeks the world over for its highly flavourful and incredibly rich pot still rums. It also produces a wide range of marks, OWH being the lightest, and DOK the heaviest (1600g/hLAA esters, the legal limit in Jamaica). I particularly like <>H and HLCF marks, for their aromas of burning rubber, seawater, rotting anchovies and fermented olives. Hungry yet? There are good official bottlings by Hampden - HLCF overproof and Great House being my favourites - and tons of indies as well. They also have an official bottling aged in sherry casks called Pagos. They all can be a bit pricey due to the high demand for this very charismatic distillate. If you seek bold funky flavours in whisky give Hampden a try.

Guyana

Rum’s Loch Lomond distillery (British tradition)

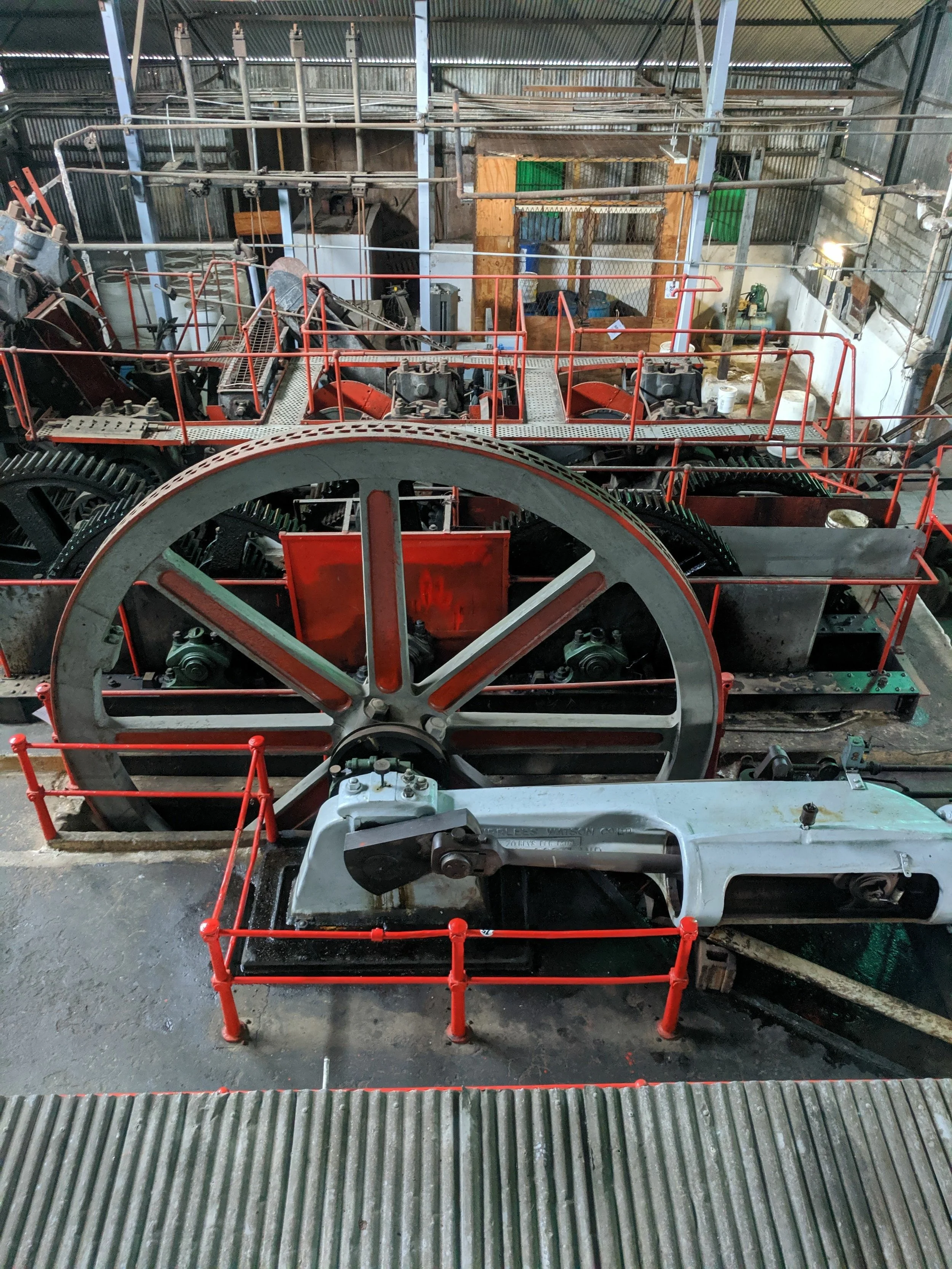

Diamond distillers on the river demerara

I titled this subchapter “Guyana”, but I could very well have written “Diamond distillery” as well. You see, in Guyana, there’s only one active distillery, Diamond, which is run by DDL - Diamond Distillers Limited - Guyana’s monopoly on rum production. By the way, Guyana rums are also called Demerara rums, as the distillery is located next to river Demerara. There used to be other distilleries in the country, but they were eventually closed and some of the stills moved to Diamond distillery. Some of these distilleries’ names, such as Enmore or Uitvlugt, live on as distillates currently made at Diamond using the original stills. As a former British colony, it used to provide a lot of the rum that was given as a daily ration to Royal Navy’s sailors until “black tot day” in 1970.

Demerara rum must be aged in wood by law, but when you get geeky, it’s all about the stills. They have a variety of different stills, from very modern MPRS columns to wooden retort pot stills. Yes, wooden as in made of wood. The MPRS and Coffey stills are used to produce fairly light rum, destined to be blended and not that interesting on its own. There are a few worth noting though:

Port Mourant: My personal favourite of the DDL marks, Port Mourant, also known as PM or sometimes Port Morant, is arguably made from the most famous rum still in the world. Consisting of two vats made out of greenheart wood, and with some parts as old as 1732(!) and copper swan necks and Lyne arms, it makes a very recognisable oily and rich style of rum.

Versailles: No, we’re not 20km south west of Paris, but in Guyana. The still coming from Versailles estate is also a wooden pot still, but it only has one vat. It makes the marque called VSG, a slightly lighter style of rum compared to PM, but still quite rich and full bodied.

Diamond High Ester: Also known as DHE, it’s a double retort pot still making rums from months-long fermentations. One of the funkiest rums in the world, but extremely rare as a standalone bottling.

Enmore: Making the famous EHP marque, it is the only surviving wooden Coffey still in the world. The analyser column even has wooden plates! While a column still, it still gives a rum with medium to high oiliness. One of the more common marks to be found amongst indies, and a proof that column still rum can be delicious.

Savalle: DDL owns two Savalle stills, consisting of four columns. They are used to make a variety of light to medium bodied rum marks, such as Blairmont (replicating the eponymous closed distillery character), LBI (La Bonne Intention - same idea), SWR (Skeldon, another long closed distillery), or the more famous Uitvlugt. A Swiss army knife of a still if there ever was one.

There is much more information online about these heritage stills, such as on Matt Pietrek’s brilliant websites Rum Wonk and Cocktail Wonk (there’s also a bonus interview with Matt towards the end of this article!).

It’s worth noting that DDL has had the habit of lightly sweetening its rum with caramel while still in cask, at the beginning of ageing. They claim they’ve stopped this practice now, but older rums might have some residual sweetness. A bit of a shame, but old PM or VSG are so flavourful that one could almost forgive them for that. We’re not talking syrup-like quantities of sugar anyway.

DDL’s own brand is called El Dorado, and I’m sure that most of you can get it one way or another, as it is widely distributed. I tend to favour the 15yo as it is to me the best value in the range, with its fruity-yet-liquorice, caramel roundness. But of course, Diamond’s rums shine as indie bottlings. There are lots of rum blends featuring Demerara rum heavily, like Elixir distiller’s Black Tot brand, or Pusser’s. There are also single cask bottlings aplenty.

Barbados

If you like Bourbon, look no further (British Tradition)

Barbados, along with Jamaica and Guyana, forms the holy triangle of British-style rum production. But like its “neighbours”, it doesn’t sport that many distilleries, in fact, only four! Barbados is known for molasses rums which are often a blend of column and pot distilled spirits, aged in casks, showing sweet aromas of coconut, vanilla and grilled bread. There are higher ester, more fruit driven styles, but they are rarer. Let’s dive into the distilleries a little:

West Indies Rum Distillery (WIRD): The biggest producer on the island, belonging to Maison Ferrand. That’s why a huge proportion of Barbados rum used in Plantation/Planteray bottlings are from WIRD. It is a very typical Bajan (Barbadian) style of rum, easy and approachable, but not uninteresting. There are plenty of independent bottlings available at higher strengths as well

Foursquare: One of the most highly regarded rum distilleries in the world, in no small part thanks to its owner Richard Seale’s energy to give Barbadian rum proper recognition. Foursquare makes different distillates, which you’ll most commonly find under the Doorly’s, Real McCoy and R.L. Seale’s brands, but also as cask strength original bottlings and amongst indies. Foursquare rums are blended between the column and retort pot still distillates before being aged. They’ve also started using fresh cane juice again, though that is still quite rare to see on a shelf.

Saint Nicholas Abbey: A rather recent distillery, but one that basically doesn’t sell to indies and only bottles at a measly 40%. Don’t waste your time on it.

Mount Gay: Quite a famous brand, often delivering quality rums at a reasonable price. Special editions at higher strengths showcase the distillery’s potential, while entry level bottlings are perfect cocktail utility rums. Good, but frankly not as good as Foursquare.

Trinidad & Tobago

You don’t know what you’re getting but it might be good (British Tradition)

Trinidad is only home to one distillery currently, TDL (Trinidad Distillers Ltd), making the ubiquitous Angostura brand. Yes, they also make the famous cocktail bitters. Their own bottlings of rum are unfortunately a bit lacklustre, as they are often sugar-laden. There are however countless indie bottlings of TDL out and about. Some are garbage, most are good, and some are just brilliant, and no one knows why.

TDL is definitely a try before you buy distillery, but when it is good, it can be outstanding value, showcasing ripe tropical fruits as well as spices and barrel ageing notes. Quite an approachable style of rum when well made.

Caroni

I could not write a feature on rum and not mention Caroni distillery though. Think of Caroni as rum’s Brora. It closed in 2002, and has since gained a cult status, mainly thanks to brilliant single cask bottlings by Italian bottler and importer Velier, run by Luca Gargano. Casks of Caroni are still bottled from time to time, though stocks must be drying quickly now, and they can fetch quite high prices at auction, from 150€ up to 5000€. Caroni is famous for its very industrial style, quite rich, with notes of petrol engine fumes. Come to think of it, think of Caroni as rum’s Springbank. I urge you to try some if you get the chance at a bar or thanks to a friend, but acquiring a bottle might be out of the question for the majority of us mere mortals.

Belize

Famous for more than a big blue hole (Spanish Tradition)

To be frank, I only included Belize as I felt it would be very snobby to not mention at least one Spanish tradition rum producing country. Belize rums stem from the country’s only distillery, Travellers Liquors, and they are in my opinion the best rums amongst the Spanish-style classics like Guatemala, Panama or Colombia. That said, they still are fairly light and approachable, modern, column still spirits and as such will never reach Jamaican-like levels of complexity. They are however often good value from indies, and some I’ve tried have been surprisingly enjoyable. Do not dismiss them, but if you’re only going to buy one bottle of rum, I’d say don’t bother seeking them either.

Martinique

Allons enfants… (French Tradition)

Home sweet home. Well, sort of. Martinique, in the French Caribbean, is French, but I’ve never been there, as it sits about 8000km from Paris. Geographic concerns aside, Martinique is the most renowned of the French rum terroirs, and that’s for one reason: Rhum Agricole, aka column distilled pure cane juice rum. Make no mistake, there are distilleries in Martinique and other French DOM (Départements d’Outre-Mer, Overseas territories) making what they call “traditional” rum, in fact quite a lot of it is produced, especially in La Réunion. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves here.

There are historical reasons as to why the French Antilles switched to producing rum from cane juice rather than molasses, but as I’m no expert, I’ll leave it up to you to check out this article from Matt Pietrek for more info on that.

In the end, Martinique is known for Agricole Rhum made from cane juice. Freshly cut cane is very fragile, so fermentation has to start less than 48 hours after harvest. That means the distilleries work basically non-stop during spring and shut down for the rest of the year. That might be one of the reasons to explain why Rhum Agricole regulations impose the use of column stills.

They have to work very fast before distillation, but quality producers are then adamant on taking time afterwards, letting rhums rest for however long they need, even white unaged varieties. There’s this belief, and I don’t know how much of it is backed by science, that, in my humble experience, letting unaged spirits rest for months, or even years in inert containers - stainless steel vats in most cases in rum production - does a lot, especially for alcohol integration. By that I mean the sensation of there being less alcohol percentage than there really is.

Rhum Agricole is always unsweetened and will always exhibit aromas of fresh cane juice, which is quite grassy, as well as fruits, spices, and earthy aromas depending on the distillery and ageing.

Rhum Agricole is not everything in Martinique though, as there is one distillery called Distillerie de la Baie du Galion producing a range of molasses-based rums, including the revered Grand Arôme, which is basically the French version of long fermentation, high ester rum. More on that when we tackle Réunion rum.

There are a number of different distilleries and brands in Martinique, and here are the ones I humbly deem worthy of your attention:

Saint James: The biggest distillery on the Island, nonetheless producing quality rhum, especially the aged versions. I particularly like the 12 year old, and cask strength offerings. Saint James aged rhums are spicy and tertiary, and the whites are fresh and vibrant. Rhums from the Bally brand are a bit denser and fruitier, still exhibiting tons of cask influence from ageing primarily in French oak.

La Favorite: There is definitely a Favorite fan club, especially for the older versions, such as the collectible Flibuste bottlings, which are 20yo or more. Quite controversially, I actually find those a little dull and prefer their unaged versions, especially the parcel selections (a practice stemming from wine, quite common in fresh cane juice rum production), such as Rivière Bel-Air or La Digue. La Favorite rums have an earthy and rich side to them which perhaps make them slightly “unsexy” but quite complex nonetheless.

Neisson: Neisson is made at the smallest distillery on the Island, and is in my opinion, the best distillery in Martinique. The whites have a distinct floral aroma and lots of elegance, while the aged versions exhibit beautiful balance between cask & spirit. The distillery has also started to switch to fully organically grown sugarcane. High quality, often matched by a higher price compared to its peers unfortunately.

Depaz: Depaz is an old, established brand. Their white rums, while not bad by any means, are a bit middle of the road, but their aged examples are probably one of the best bets for whisky drinkers, thanks to the use of more American oak than their neighbours, bringing more roundness and perceived sweetness. The regular XO version, aged for 8 to 10 years and bottled at 45%, is great value here in France.

JM: JM makes great value rum, and is also known to be located in what is probably the most beautiful setting for a distillery, in the middle of the Jungle. The whole range is solid value, be it the whites or aged versions, and exhibits fruity aromas alongside the signature agricole grassiness.

Baie des Trésors: The owners of the brand used to be purely sugarcane growers, and sold their production to distilleries like Saint James. They have recently started to retain the canes from their best plots to be distilled by Saint James and then sold back to them. Everything is bottled plot by plot, with no blending, and at high degree. Still young, but showing lots of promise imho.

A1710: Established in 2006, A1710 is special in the sense that it doesn't use a column, but rather something resembling Loch Lomond’s straight neck pot stills. They distill from both raw sugarcane juice and molasses, and they produce some incredible white rums, often bottled at more than 55-60%, and exhibiting very noble floral and truffle aromas. Unfortunately, the prices are unfortunately a bit out of hand in my opinion.

Guadeloupe & Marie-Galante

Getting geekier about agricole rhum (French Tradition)

Guadeloupe is another Island in the French Antilles, and Marie-Galante is another separate Island next to Guadeloupe, but legally part of Guadeloupe, and as such included in the Rhum geographic indication.

Guadeloupe’s regulations differ slightly from Martinique, in the sense that they can use pot stills and still be labelled as Rhum de Guadeloupe - though not Rhum Agricole de Guadeloupe, which remains purely a column still product, and the Island’s most renowned output.

Montebello distillery, Guadeloupe

Again, you can find it aged or unaged, and no sweetening is authorized, which is always good news. There are a few distilleries/brands putting out great rum from Guadeloupe and Marie-Galante, and here are my favourites:

Longueteau: For me, the best of the Island, and maybe even better than its Martiniquais counterparts. Longueteau were among the first to experiment with “sélections parcellaires”, which means separating canes grown on different terroirs and individual plots, and bottling them individually once turned into (often white) rum. They also recently released the “Harmonie” collection, which consists of Agricole rhums aged 2, 4 and 6 years, and bottled at cask strength, with no colouring or chill filtration. If that’s still not interesting enough for you, try their “Genesis” collection which is composed of unaged and aged rhums which have never been reduced, at any point - also called “brut de colonne” or still strength. Yup, that means 70%+. They also produce the Papillon brand, which is good value and made from sugarcane they buy - if I understand correctly - rather than grow themselves. Longueteau rhums are precise, mineral and showcase a delightful star anise vegetal character.

Bielle: A quite famous name from Guadeloupe, which you’ll commonly find among indies, though often at high prices unfortunately. Longueteau is to me the king of white rums, and some could argue that Bielle is the queen of aged rums. They have some fantastic 10, 15 or even 20+yo Rhums, but unfortunately, the price of them can often be dissuasive. Bielle rhums are definitely enthusiast oriented, as they can be quite tough to love at first sight: oily, grassy, earthy and complex.

Montebello: Relatively unknown compared to those first two names, Montebello rhums have long suffered with a reputation for being supermarket fodder, yet in the last ten years they have turned themselves around and propose really good value offerings as well as interesting cask experiments bottled at cask strength, and are making a comeback among enthusiasts. They are known for storing casks in containers in the scorching equatorial sun, which leads to massive evaporation and concentration of flavours. Montebello rhums are a perfect introduction to agricole rhum, as they are quite fruity: citrus, pineapple, along with that classic agricole grassiness.

Père Labat / Distillerie Poisson: Famous for its high octane white rhums - the 59% white rum leading the pack. A quite balanced style, that some say is the best of the two Islands. While I don’t personally agree with that last statement, it is a quality rhum, and you should give it a try if you get a chance. Classic grassy, cane-juicy agricole rhum.

Papa Rouyo: They make pot still, pure cane juice rhum at Papa Rouyo and that’s always interesting. They are also very new, so no massive age statements yet, but the white rums are still interesting to taste - as is the case with all those distilleries. They have a fruity and floral component, as well as a nice mouthfeel, no doubt due to the aforementioned pot stills. A bit pricey though.

Karukera: Though they produce some whites, Karukera are specialised in aged agricole rhums, often with more wood influence than most. They can be interesting though, as they offer a clear contrast to the norm.

La Réunion

A hidden gem worth seeking out (French Tradition)

The third of the French rum producing Islands, La Réunion is quite far from Martinique and Guadeloupe, being located in the southern Indian ocean, not far from Madagascar. Réunion rhums are often overlooked, even sometimes by rum connoisseurs, because of a perceived lack of high-quality rums. It still suffers from a bad reputation to this day, even in France, because of supermarket rhums in the 2000s. That is slowly starting to change though, and in no small part due to one distillery’s output being constantly phenomenal.

Savanna

There are, these days, other distilleries making good rum on La Réunion, such as Isautier or Rivière du Mât for example. Be careful though. Avoid anything with the name “Charrette” on it like the plague. But none come close to the perfect gem that is Savanna. Savanna became famous with their HERR bottlings: High Ester Réunion Rum. These are pot distilled, long fermented, high octane rhums, similar in some points to funky Jamaican or Haitians, yet distinctly different.

By the way, producers from La Réunion tend to use a majority of molasses rather than cane juice to make their rums, which is a change from the French Antilles. Savanna also produce aged rhums, as well as different white rums, including an agricole (so - cane juice) and one called “Lontan”, which is another high ester rum, this time column distilled, and generally a bit more available than the allocated, collectible HERRs.

I love Savanna, it is one of my favourite rum distilleries, and the only name you should really focus on remembering from La Réunion for now. If you come across a bottle, do try it, especially the high ester stuff which is just magic.

Haïti

Resilience and craftsmanship (French Tradition, but really its own thing).

One could consider Haïti to be a French style producer of rum, as they almost always use fresh cane juice; but to be fair, Haïti is its own thing - and has always been, being the first Caribbean country to declare independence from a major European power in the late 1790s.

Haïtian rum is locally known as clairin, a name which refers to the clarity of the unaged spirit, which is often how it is consumed. Each clairin producer really has its own style, because this is not a properly regulated spirit. After all, they have more pressing matters to deal with over there unfortunately. Some distillers use cane juice, others cane syrup, the fermentation times vary, most don’t add yeast and let the indigenous varieties ferment the wort, or vesou as it is called there, and the still types, sizes and shapes vary tremendously. There’s even one distillery called Casimir that ferments their cane juice in mango tree vats, while adding lemongrass, ginger and cinnamon to the vesou!

In my experience, there’s no bad clairin among the ones that make it all the way here. You can trust names like Sajous, Le Rocher, Casimir, St. Benevolence, Providence or Vaval. They’re often quite affordable as well, hovering around the 50€ mark around here. Granted they’re unaged, but they are complex flavour bombs and I urge you to try them provided you get the chance to.

Haïti also hosts one more conventional rum distillery, which won’t advertise themselves as clairin: Distillerie Barbancourt. Barbancourt was founded in 1862, and produces pure cane juice rum using modern column stills. They offer a wide range of aged rums, and are generally easier to find in Europe and the US, but they are more oriented towards beginners and cocktail enthusiasts. The prices tend to be lower than for clairins though.

Other rum-producing countries

I don’t have the time nor the proper knowledge to tell you about all rum producing countries and territories in detail, so let me just quickly mention a few interesting ones here.

Brazil (Portuguese tradition, but also really its own thing)

Portuguese-tradition rums are rarer than the other ones, but Cachaça - which is just the word for Brazilian rum - is clearly the most famous (the others come from Madeira and Cabo Verde). Cachaça is always produced from cane juice, and the differences between cachaças comes from all the different cane varieties, terroirs and distilling techniques. It is a world in its own right, and a spirit every self respecting Brazilian will defend to the death. Most are left unaged, or aged in inert containers, but some are aged in wood, and quite interestingly, rarely in oak but rather in indigenous Amazonian woods, like Amburana for example. There are some stunning examples of Cachaça, and some good ones even make it to Europe and the US. I like the “Engenhos da vertente” and “Magnífica” brands.

Grenada (British tradition)

Grenada has been in the spotlight recently, as their most famous rum distillery, Renegade, had to stop production for financial reasons. Renegade was Mark Reynier’s foray into rum production, where, in my opinion, his terroir approach laid on much stronger foundations than for Waterford. There’s also the rum known as “Rivers Antoine”, which is a 69%(!!), high ester, unaged, intense-as-hell beverage. Basically, clarified petrol at this point. Needless to say, I love it.

Antigua & Barbuda (British tradition)

Antigua is one of the many countries where rum production is controlled by the state at a single distillery. They produce various brands there, but the most famous one worldwide is without a doubt “English Harbour”. Their range is often very good value, and tasty as well. An approachable, molasses-driven style of rum, perfect to get introduced to the category as a whisky drinker, especially their wood finished range, which regularly features sherry or port finished rums bottled without additives or chill filtration, at 46%, and priced around £40. Recommended buy for the sherry bomb aficionados.

Saint Lucia (British tradition)

Copy & paste, really. Government controlled, small Caribbean Island, molasses based, column distilled. The most global Saint Lucian brands are “Chairman’s reserve” and “Admiral Rodney”. The regular ones are every day sippers or cocktail oriented, but there are occasionally stunning well-aged examples, be it official bottlings or indies.

Fiji (British tradition)

If you don’t drink rum or watch rugby, you might never have heard of the pacific archipelago nation that is Fiji. On top of producing some of the best wingers and outside centres in the world, they also have time to make some rum, at the Rum Co. of Fiji distillery, formerly known as South Pacific Distillery. They use molasses, long fermentation times and a mixture of columns and pot stills to make a style resembling something like a blend of Barbados and Jamaican rum, and I mean that as a compliment.

United States (British tradition, but really its own thing)

One could be forgiven for thinking that rum production in small distilleries in the US is a new thing linked with the resurgence of modern craft distilling, as it all but stopped during and after prohibition, only to restart in the 2000s. But Caribbean molasses were indeed imported into the USA during the 19th century, and there were quite a few rum distilleries, especially in New England and along the east coast, to the point that rum was the most consumed spirit in the country at the end of the 1800s. These days, rum production in the USA is a craft distillery thing, and just like their single malts, very little makes it out of the country, as they are apparently quite thirsty over there. The most recognisable brand outside of the US is probably Privateer, made in Ipswich, Massachusetts.

Australia (British tradition)

Yes, they make rum down under, mostly from molasses, and usually age it. I get the idea that one of our resident aussies could tell you much more about it, so I’ll keep it brief. The oldest and most recognisable brand is “Beenleigh”, a distillery producing rum from both pot and column stills. Quite good rum in fact, balanced between sweetness, fruitiness and freshness.

We Need To Stop Somewhere

There are many, many other places where rum is made on this planet - metropolitan France, Thaïland, Indonesia, Canada, Mexico and even Islay - but I have neither the time nor the sufficient knowledge to write about them here. If you want to know more about rum, let me once again advise you to read Matt Pietrek’s books and blogs, as well as Dave Broom’s book on rum. You can also check whiskyfun.com on Sundays, which is Serge malternatives day, often dedicated to rum.

As for us here, I thought we could end this feature with an interview, as well as tasting notes. I will score the rums I’m going to taste, but only because I feel like it can give you a better idea of which ones I prefer, and mostly because it is fun. Please take these scores with a grain of salt, this is not a rum review website after all.

Matt Pietrek

Matt is one of the most influential persons in rum, being an educator, blogger and author. Think of him as Rum’s Dave Broom. His book “Modern Caribbean Rum” is nothing short of a rum bible. He also writes a lot about cocktail culture, notably the Tiki movement, in books such as “Minimalist Tiki” and “Polynesiacs”. Matt also regularly posts on his two blogs: Rum wonk and Cocktail wonk.

AF: What factors do you think helped rum become one of the most enjoyed spirits on the planet?

MP: The diversity of flavor profiles is a big part of rum’s resurgent popularity. Being a multi-spirit “meta-category” like whisky or brandy means that rum isn’t confined to the fairly similar flavor profiles of a single country spirit like Scotch whisky or cognac. Jamaican white overproof rum, deeply complex Demerara rum, and magnificent rhum agricole from Martinique couldn’t be more different, yet all fly under the “rum” banner. The affordability of rum relative to “super-premium” spirits like Single Malt Scotch and bourbon also helps bring people over from those spirits.

AF: What would be, in your opinion, a good introduction to rum for a whisky drinker ? You wrote an article about Barbados and Bourbon drinkers if I recall correctly…

MP: It depends on how adventurous and willing they are to go outside their comfort zone with whisky. For someone who wants to dip their toe into the water while retaining the comfort of strong ageing flavors, Barbados rum like Mount Gay offers that. The rums from St. Lucia Distillers, particularly the Chairman’s Reserve line, are a little more adventurous without going into deep waters. For those who want to immediately jump into the deep end, aged Jamaican rums from Hampden Estate, Long Pond, and Worthy Park fit the bill, as do high-strength Demerara rums, unaged rhum agricole, and Haitian clairins.

AF: What do you look for when browsing for your next rum bottle?

MP: I’m somewhat an outlier, as I have hundreds of rums across a vast swath of rum styles. I look for rums in which I have little or no experience—an increasingly rare proposition! For people newer to the rum space, some incredibly good rums are in the 50-to-150 euro price point. You can spend more, but learn what tickles your fancy first. Also, don’t be afraid of unaged rums! There are some magnificent examples.

AF: You have visited a number of rum distilleries. If there’s one aspect of rum production that’s more talked about than in whisky, it surely is fermentation times. Do you think a longer fermentation is a guarantee of a good rum? How do you think that these concepts could transfer to other spirits such as whisky?

MP: Fermentation is key to the flavor of many rum styles. But fermentation length is just one dimension. It’s not about just letting your fermentation run longer. Some rum fermentations use yeast strains similar to those used in whiskeys and take about the same time as whiskey fermentation. However, other rum fermentations use more exotic yeast strains. They take longer and yield less alcohol but make huge amounts of flavor compounds not typically found in whiskey.

AF: There is also a lot of debate among rum enthusiasts on continental versus tropical ageing. Could you briefly explain these concepts as well as state your opinion on the matter?

MP: In a nutshell, ageing is the result of several types of chemical transformations—all going on simultaneously! Flavors are extracted from the cask walls, while water, ethanol, and flavor compounds are evaporating through those same walls! Plus, the flavor molecules are constantly reconfiguring themselves into other flavors.

Naturally, the environment where a cask resides, including the ambient temperature, humidity, and how deeply they oscillate, influences these transformations. Warm environments like the Caribbean speed up certain transformations, especially evaporation, aka angel’s share.

Likewise, cooler environments like Scotland slow down some transformations. It’s often said that rum “ages faster” in the Caribbean than in Northern Europe, but that’s an oversimplification. However, we can say you will notice the effects of ageing in a warm environment sooner than the same rum cask in cooler conditions. However, cooler conditions and the right cask can let a rum mellow much longer — decades, without it becoming overly “woody.” Neither environment is better—they’re just different. For centuries, most rum ageing occurred in cool European climates. The famed London Dock Rums are one example.

AF: Finally, since this article is about finding alternatives to our favourite spirits, what are your preferred alternatives to rum?

MP: While I love most distilled spirits (not so much vodka, though), I have a particular fondness for brandies, including the non-grape types like Pisco [Pisco is actually made from grapes, your insufferable editor notes] and Calvados. Within the whiskey domain, I’m drawn to peated malts. I spent my 50th birthday touring Islay’s distilleries!

Massive thanks to Matt for being so reactive and open to this. Check out his work if I’ve managed to get you interested in rum.

Now, let’s get some rum in our faceholes!

Review 1

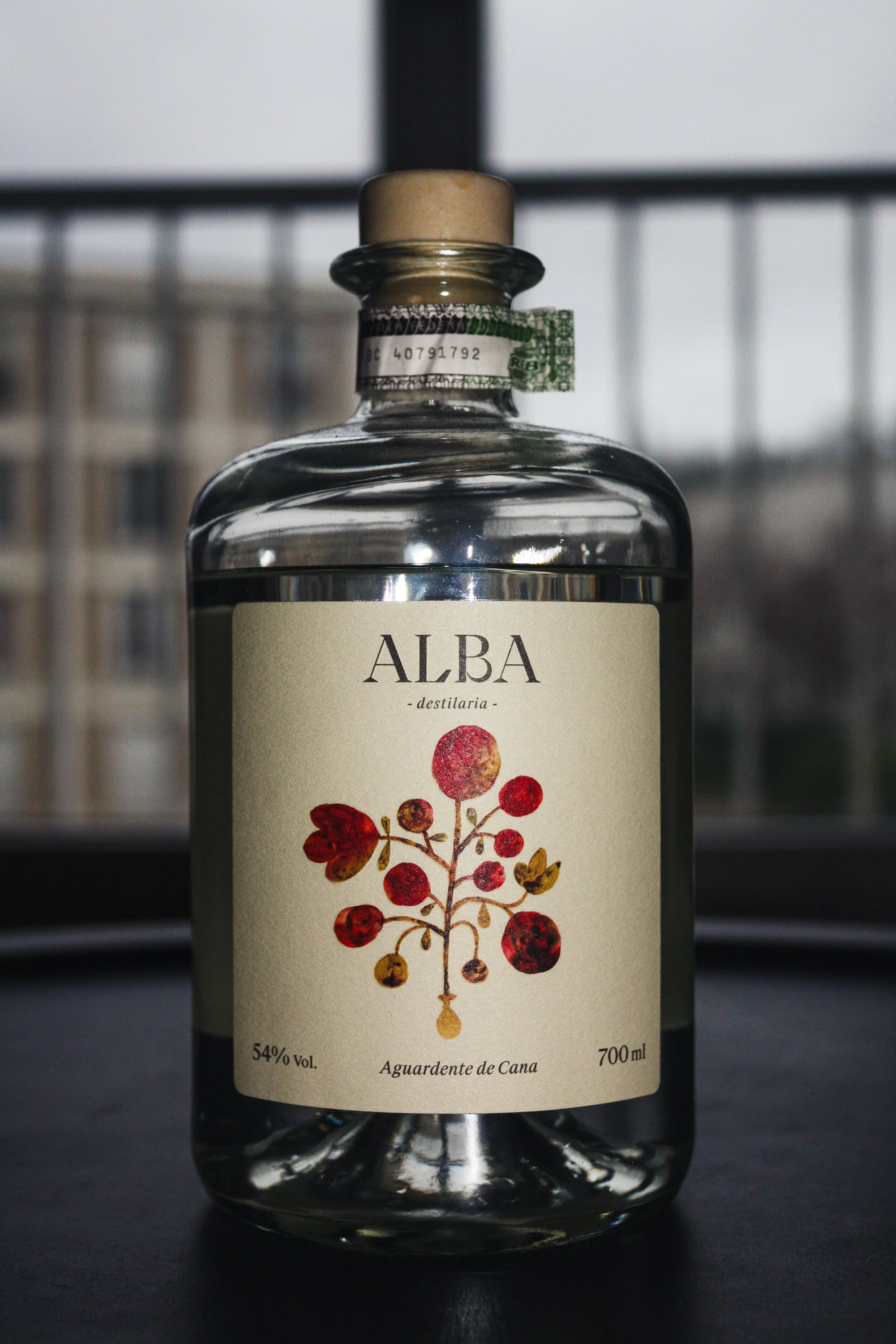

Alba Aguardiente de Cana, pot distilled, unaged Brazilian rum / Cachaça, red cane variety. Natural presentation, 54% ABV

£ - gifted, only available in Brazil

You might remember when I told you about my first meeting with my Brazilian pal Pedro, last year. He had brought whisky, but some Cachaça as well, and I got to bring back this bottle here as well as the next one. This is special, as both hail from distilleries whose output isn’t exported to Europe due to their size.

Aguardiente de Cana just means Sugarcane brandy, ie. rum. Or cachaça. It really doesn’t matter, because it is very good. Interesting detail, this one is pot distilled, which is less common of the widely exported cachaças.

Score: 9/10

Exceptional.

TL;DR

Beautiful, elegant, clearly made without cutting corners; an exceptional drink

Nose

Very fresh and vegetal. Radish, celery and fresh carrots. A basket full of freshly picked veggies, which reminds me of summer afternoons spent at my Grandpa’s - picking carrots and tomatoes. Soft pink pepper, and delicate white flowers. An earthy side as well, but only a hint. Almost coastal. A sudden burst of Dijon mustard, with the seeds.

With water: More of the same, with added wet clay and plaster. The mineralic aspect is definitely amped up. A quick burst of strawberries and heavy cream.

Palate

Taut, mineral, turning into a diluted rose syrup on the finish. Super elegant, with an impressive alcohol integration, and a hint of salinity. Fruity finish, like a green banana.

With water: sweeter arrival, on those floral syrups, but the vegetal aspect is still front and centre. The creamy strawberry note also appears on the palate.

The Dregs

This is such an elegant and complex spirit, absolutely brilliant in every way. There is length, development, complexity, refinement, intensity and class. This is truly something that has been made with knowledge and attention to detail, without cutting corners. A very fine drink.

Score: 9/10

Review 2

Cachaça Canarinha, 60cL bottle, Brazil, aged in Baume wood for 4 years. Believed to be natural in every way. 44% ABV

£ - gifted, only available in Brazil

This was also gifted to me by Pedro, whom I thank very much. This cachaça is bottled in a beer bottle, as an homage to all the small producers using whatever glass they could find. They even include a fake beer stopper for when you pop the capsule. This particular cachaça has been aged for 4 years in a type of wood called Baume. Brazilian indigenous woods often give textures and aromas that are wildly different from oak, so we shall see what this one is capable of.

Score: 6/10

Good stuff.

TL;DR

Looks like a beer, but definitely tastes like its own thing

Nose

First of all, visually, the 4 year ageing period in a tropical climate was only able to give it the faintest of golden hues. Earthy, potting soil, vegetal. Wet exotic woods and forest floor. There’s even some smoke, in a very unique way, and the lower alcohol level makes it dangerously drinkable. The grassiness synonymous with cane juice rum is there, but subdued by the ageing.

With water: Fresher, fruitier, but a bit blurry. Hint of diluted cider vinegar.

Palate

Round, oily and sweet, but herbal as well, like a mint & sage syrup. Great mouthfeel. Sweet lemon candies.

With water: Szechuan pepper, mint, parsley and coriander leaves - cilantro if you’re across the pond. There’s a very unusual light “numbing” effect on the palate throughout the whole tasting, I suspect due to Baume wood.

The Dregs

This is unique, unusual, even for a cachaça, and as such, very much fun to drink. Not that complicated, but it’s an interesting one to dissect. Again, many thanks to you, Pedro. See you at Whisky Live Paris 2025!

Score: 6/10

Review 3

Neisson Blanc, rhum agricole, Martinique, cane juice, column still, 1 Litre bottle. Believed to be natural in every way. 55% ABV

€30 (£27) paid, widely available in France and elsewhere

This is an ubiquitous bottle of Agricole rhum from Martinique, made by what is in my opinion the best distillery on the Island, and sold dirt cheap. The fact I can pick this up at many supermarkets for less than 35€ blows my mind, even though I really don’t like to buy booze at supermarkets. It is not Neisson’s most revered bottling, but let’s see if it sets the standard for the higher end ones.

Score: 7/10

Very good indeed.

TL;DR

Good, available value, without tasting ‘cheap’

Nose

Lemon, tart orange juice and cane syrup. Creamy yoghurt, slightly fermenty. Savoury, cut grass from a week ago. Lemongrass and yuzu liqueur.

With water: flamed bitter orange peel, burnt citrus oils. The finish exhibits a vegetal/earthy side reminiscent of dry vermouth.

Palate

Quite viscous for a column still distillate, no doubt helped by the low collection strength (70-75%) and the ABV. Pink pepper, and the classic Neisson flowers. Mineral finish, after a sweet and juicy peach note.

With water: Even richer somehow, juicy pears, all sorts of grasses and a delicate spicy finish.

The Dregs

This is the Springbank 10 of Agricole rhum. A classic benchmark, which despite being affordable - in this case, VERY affordable - sets the standard for the rest of the distillery’s output. I’ve been lucky to try various Neisson as part of my job, and they always are high quality, this one being no exception.

Other opinions:

Score: 7/10

Review 4

Savanna Lontan, High ester white rum, La Réunion, molasses, 6 days long fermentation, column still, 932,32g of esters/hL, 1500 bottles, believed to be natural in every way, 57% ABV

€45 (£40) paid, annual release, now sold out

Lontan is a yearly release by Savanna, consisting of a high ester rum (called grand arôme in France), made from molasses that have been fermented for 6 days, before being distilled in a Savalle column. It is not aged in wood but rather spends 11 months mellowing in a steel tank.

I love Savanna, especially for their grand arôme rums, like Lontan and HERR - though they make a mean Agricole called Créol as well! Let’s see what this one is about.

Score: 7/10

Very good indeed.

TL;DR

It will slap you in the face and you’ll like it

Nose

Dozens of litres of pineapple juice. Black olives and anchovies in brine. Fruity yoghurt, peach, and pineapple. It is very intense. A mineralic side appears, evoking rock pools and rotting algae. Fermenting grass. Hint of rose water.

No change with water.

Palate

Rich, salty, umami, fruity, mightily intense. Bright and fresh, yet oily, rich and long. No change with water as well, it still has this incredible density.

The Dregs

This is one of the most potent spirits I’ve ever tasted. It really hits you neat, and it makes a characterful daiquiri as well! I love it, even if it is not that complex for a high ester rum, it is so massive that it is puzzling. Think, this is column-still distillate, so you can only imagine how the HERRs taste, with 11-day long fermentation and pot distillation!

Other opinions:

The Lone Caner (different batch)

Rum ratings (various batches)

Score: 7/10

Review 5

Privateer Navy Yard, cask strength single cask, barrel #P531, virgin oak barrel, molasses, USA, believed to be natural in every way, 54.6% ABV

€80 (£70) paid, various single casks available in the US and Europe

Privateer is without the shadow of a doubt the most renowned craft rum distillery in the US, in no small part thanks to Maggie Campbell’s early work there, before she moved to Barbados. Privateer is known for primarily ageing rum in virgin white oak barrels, just like bourbon, thus having a very wood forward style. Their core range is good but a tad simple, but they release lots of single casks through their Navy Yard range. This is one of those single casks, imported by la Maison du Whisky. They’re all NAS to my knowledge, so quite young, but the wood makes itself known. I believe this to be fully natural, with no colouring, chill filtration or added sugar.

Score: 6/10

Good stuff.

TL;DR

If there ever was a rum for bourbon lovers

Nose

Very reminiscent of Bourbon. Varnish, caramelised peanuts and brown sugar on the first nose. Fruits hidden underneath, mainly ultra ripe bananas and grilled pineapple. Vanilla ice cream, and raisins. Well, maybe a rum & raisin ice cream then!

With water: Creamier, vanilla cream filling, flan, and coconut cream. Bit less varnish. Sweet popcorn.

Palate

Rich and sweet, with vanilla and runny caramel. Quite long, on brown sugar, with a really good alcohol integration.

With water: Doesn’t change much, maybe gets creamier, echoing the changes on the nose.

The Dregs

This is a good, sticky rum, for when the mood for something sweet hits. It will definitely please the cask strength Bourbon enjoyers, as the cask does a lot of the heavy lifting. A recommended buy if you have a sweet tooth and find this at a good price, which I suspect is easier for those of you who live across the pond.

Other opinions:

The Fat Rum Pirate (different batch)

The Lone Caner (different batch, but also a recommended blog to read)

Rum ratings (various batches)

Distiller (various batches)

Score: 6/10

Review 6

Hampden Great House, 2022 edition, High ester, molasses, retort pot stills, Jamaica, NAS, believed to be natural in every way, 55% ABV

€150 (£135) paid, sold out, yearly limited release

I bought this bottle in a Parisian shop specialised in rum, specifically for this feature. I’ve long wanted a quality Hampden at home, and I recently felt that the classic 8yo wasn’t as funky as it used to be, and as such I didn’t like it as much as the rest of the range.

So I entered this shop, which is run by a good friend of my boss. I knew from him that business wasn’t doing well, and that’s why I decided I was gonna help out by purchasing a bottle. Since this bottling of Hampden is somewhat of a collectible, the price was above RRP, but within acceptable limits, sorta like a Springbank 12 at £90 instead of £70. I grabbed it, knowing it wasn’t going to disappoint anyway, as this is my style of rum.

Score: 8/10

Something special.

TL;DR

I’ve paid too much for a reason

Nose

The first impression is of a coherent, classic Hampden. I believe this bottling is blended not to showcase any particular marque, but rather to present the quintessential Hampden style of rum.

It is dense, with overripe exotic fruits, and a tropical forest floor. At least how I imagine it smells. Wandering through the jungle has always been a dream of mine. It is also rubbery, and has hints of tar and green olives. Mango and pineapple syrup take the lead. Though it is aged, between 3-11 years, the casks have very little influence on it at first. Distant menthol and burning plastic.

With water: Maybe a tad more earthy and fermenty now (lactic), but also a bit quieter. Spices like cinnamon and clove appear.

Palate

Noticeable acidity, surely due to the use of dunder, or even muck. This is, as the Savanna, remarkably intense. Juicy exotic shrubs, but also a lot of brine and an underlying earthy side. Very good length.

With water: Arguably more balanced, but also toned down a bit. The spice from the nose carries through to the finish.

The Dregs

This is classic Hampden to me. I’ve tasted some that were a bit more intense on the briny/anchovies side, but the fruitiness in this one makes it easier to drink in my opinion. I really think that a lot of whisky drinkers, especially the ones who like bold distillate flavours like peat, salinity or wax would enjoy this one, and a lot of the other high ester rums that are present on the market.

Other opinions:

Score: 8/10

The Final Dregs

Well, this was again quite lengthy, so if you made it here, thank you for your time. I kept somewhat superficial in my explanations here, partly as I’m not as well versed in rum as I am in whisky, but also because this was long enough, right?

If you are already a rum aficionado, I hope I didn’t share too much bullcrap, and if you’re not, well, I hope you may consider trying some. As we seek to discover flavours through distilled spirits, I think rum is as valid a category to explore as whisky, and we all could do with a step-change from time to time - not to mention a surefire cure for palate fatigue..

I’ll go back to regular whisky reviews for a while, but there’ll be two more episodes in this Malternatives Series, for there are many interesting things to drink!

Slàinte!

Once again; many, many thanks to Matt Pietrek for his kindness and willingness to answer my questions, when a lot of others didn’t. I hope to share a dram of Islay whisky with you at some point.

Many thanks to Pedro for the Cachaças too!

AF

-

Dramface is free.

Its fierce independence and community-focused content is funded by that same community. We don’t do ads, sponsorships or paid-for content. If you like what we do you can support us by becoming a Dramface member for the price of a magazine.

However, if you’ve found a particular article valuable, you also have the option to make a direct donation to the writer, here: buy me a dram - you’d make their day. Thank you.

For more on Dramface and our funding read our about page here.