The Colour of Whisky

The True And The Not So True

“The first bite is with the eyes.” Marcus Apicius – 1st Century Roman culinary expert

Following on from Aengus McCloud’s excellent piece on Paradigm Spirits ‘whisky’ I thought I’d revisit a favourite topic of discussion; the colour of whisky.

From the off I’d ask you to bear in mind that I am not a specialist on the subject of colouring or compounds. I have little to no interest in the science behind any of it. I am very much the guy on the distillery tour that is mostly disinterested until we get to the tasting bit. I know how to open my bonnet and I can look at the engine, but I’m much more interested in simply driving the car.

“All the colour comes from the wood.” I’m pretty sure we’ve all heard this oft-repeated statement at some point. As recently as an online tasting during the Covid lockdown I listened to someone, who I felt should know better, repeat this misleading statement.

For Bourbon, yes, the colour is from the wood - any occasion where the wood is virgin or brand new, and the spirit going in is clear as water then it’s not really up for debate, right? But to suggest that the darker whiskies many of us love owe their colour solely from interaction with the oak is nuts and to continue to repeat the above statement I think is disingenuous. I’ll go further, I believe the Scotch whisky industry has been disingenuous about its flavours and colours for at least a century; maybe more.

Many of you will have sampled multiple blends from the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s and I trust, like me, you have noticed a very common flavour profile; sweet tobacco, pipe smoke, well-worn leather, gentleman’s club (you get the idea and for our American friends, by ‘Gentleman's Club’, think more of a Victorian smoker’s establishment than somewhere you might need lots of small notes). This flavour profile more or less vanished in the late ‘90s and frankly has never really returned. I’m concentrating on blends here, and those of the aforementioned decades are all slightly amber too; very similar in colour, body and finish. Don’t get me wrong, they are lovely and at times sublime, I’m merely pointing out that there is a thread or theme to these bottlings.

For this consistent flavour profile to exist I am going to point an accusatory finger at additives being the culprit. Either additives or mixing with substances; same difference really. I’m not referring to colouring which is legally allowed to be added (and goes back at least a century as can be seen from the blend make-up in 1923). I’m referring to other liquids being in sufficient quantity as to make an impact on the colour and or flavour.

There is an excellent article on scotchwhisky.com regarding the use of Paxarette in the industry – well worth a read – what is only hinted at though was the direct addition of Pax, as it was known, into the blended mix before bottling. Therefore, no longer just a method of ‘seasoning’ a cask, it was used as a direct tool for colouring and flavouring the whisky. On Page 143 of the quite extraordinary “The Distillation of Whisky” (collated by James Eadie from publications printed from 1927 – 1931), whilst giving colouring the briefest of mentions (even in the late ‘20s I’m assuming it was a hushed up, frowned upon subject) it states:

“…nothing is added to British Spirits in duty-free warehouses except for colouring matter (fluid caramel or duty-paid Paxarette) and water. Colouring is necessary in order to maintain the standard “Sherry” appearance which satisfies the public.”

[Worth noting here that traditional ex-Sherry casks were in high demand but low in supply.]

I have tasted Pax – it is similar in consistency to diluted E150A (the legally allowed colouring agent) but lacks the bitterness, being more like a super-reduced, fortified, raisin wine. There’s an excellent video from Ralfy (Review 888) where he tastes it and explores the history of Pax further.

From the blending ledgers of the early 1920s we can see that colouring and Pax are mentioned in the top right-hand corner. This is a postscript addition on the page so one can only deduce that this is an instruction to add after either bottling or being returned to wood for further maturation or marrying.

Anecdotally, I’m going to share a frequently whispered rumour (too much for it to be without some merit) that once-upon-a-time, whisky bottling halls would sometimes dump copious amounts of brandy into the mix to help with colour and also possibly add body and iron out certain flavour issues. In other words, make something appear and taste older than it is and no doubt the brandy was quite a cost-effective solution.

Of course, I have no video evidence of either practice and, along with Ralfy, I am not against the use of Pax (although the mixing with brandy was as shady as it comes – if it indeed happened).

It strikes me as odd that the Scotch Whisky Order 1990, which in essence did not change much from the 1988 Scotch Whisky Act with regards to Pax, would continue to allow the addition of spirit caramel but nothing else. Who decided this and why? Who was campaigning for spirit caramel but against Pax? Surely there must have been voices out there in defence of its use?

It seems to have maybe been a scapegoat – perhaps from a sudden rise in notoriety – and its removal was maybe championed by a few companies that felt they could lose it from their cask management system without detriment to their maturing and bottled products?

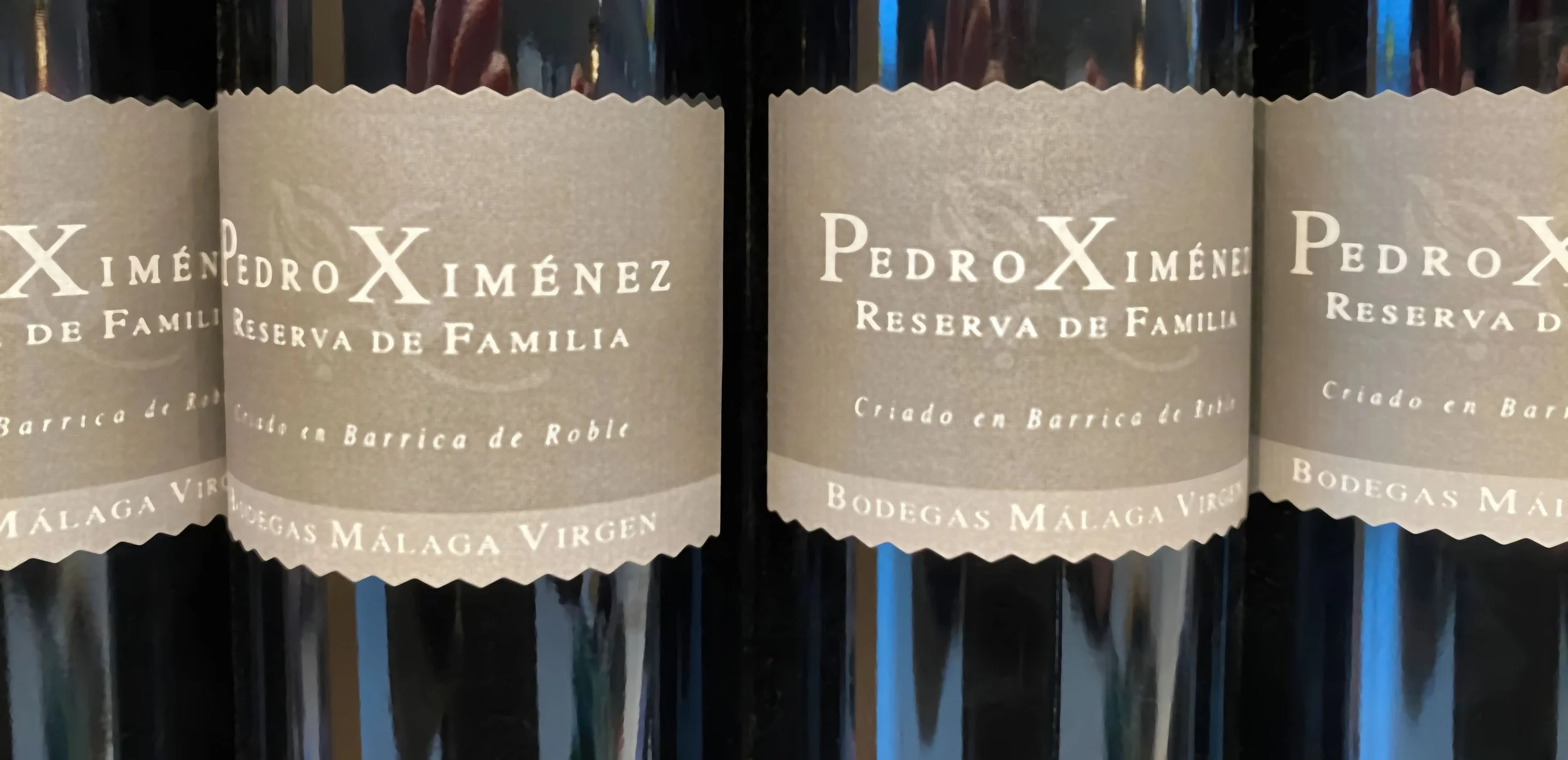

And here’s the really interesting rub from the withdrawal of Pax being used; distillers needed a substitute. Soon after the 1990 Scotch Whisky Order Diageo released details about their cask seasoning programme. Essentially the same process as injecting Pax, just using a substitute wine-related product. Around the same time, we saw the emergence of Pedro Ximenez casks being used – not seen really before this time (at least I have no evidence) – and what is Pedro Ximenez, in this context, if not a version of Pax?

As the Scotch Whisky Order is only limiting what can be added to whisky why can Pax not be used in the cask preparation process? Is it indeed banned? I’m going to suggest it hasn’t altogether disappeared (and don’t forget, this law only pertained to Scotch Whisky – hint, hint, nudge, nudge). I recall twenty or so years ago being with an absolute veteran in the industry who was examining a ‘Black’ whisky (the independent bottler had even stated Black on the label). “Can’t happen without Paxarette’” he told me. “No natural ex-Sherry cask can make a whisky go that dark.”

So that would suggest the uber-dark, near black bottlings we occasionally see are not from naturally matured ex-Sherry casks? It’s just a theory, don’t seek out someone to sue. Having worked with virgin oak casks from the US and all over Europe I can add my tuppence-worth that it is very hard for oak alone to get Scotch whisky to near Ribena-esk tones.

I think I’m right that Glenmorangie released a bunch of experimental virgin oak casks and, despite having a very good period for maturation, none were anywhere near mahogany in colour. So I conclude then that the previous contents and/or additives are making the difference when it comes to those darker coloured whiskies.

The possible hypocrisy or silliness, I guess, is that banning Pax casks was just a deflection from what was a truth; the previous contents of a cask not only make a marked difference in colour but also to flavour of the new contents. If it didn’t we would only have about 1/50th of the currently available whisky on offer. So why ban Pax when Port, Cognac, Madeira, all wines and even Tequila casks can be used legitimately? It makes no sense to me.

Especially when you add in the Pedro Ximenez element – Pax and Pedro Ximenez are just slightly different coloured chalks. And here I am kind of getting to my point about the colouring issue. As it is human nature for some reason to gravitate towards certain colours for our whisky preferences (some love their whiskies pale, most like a deep, rich colour) there is a need for whisky companies to get colour in their bottlings; but of course it has to be done naturally.

I feel there is a tendency from Scotch whisky policy makers to believe their product to be so standalone that any realisation of an actual symbiosis or benefit from anything extraneous is a slight or slander. It’s almost an Island mentality and has shaped decisions for many decades. It isn’t that long ago that the SWA tried to ban producers from referencing the previous cask contents in tasting notes and marketing. This is head in the sand stuff. There was even an attempt to suggest that some casks were traditional and others weren’t.

In a 400 year old industry this didn’t work out well in their favour (although I think the SWA did get their way banning casks that had previously matured stone-fruit products – perhaps no-one cared about this strongly enough to object). It is born from an idea that Scotch is unique and independently-unique. Both sentiments are flawed. Make it a solely island-sourced product and we’ll run out of oak real soon – and even if we did have enough oak it wouldn’t taste anything like what we consider to be Scotch whisky anymore.

Anyway, back to colour. It is undeniably important - especially when not contrived from additives. Colour is unequivocally, I hope I’ve established, influenced from the previous contents and this can very much depend upon how ‘wet’ the casks are when transported. If you look at how the story of maturation began, this was the emptying, either in a house or warehouse, of one product from a cask and the filling of it with another.

There are no records of discovery, patent, or design of this happy accident but we do know that time in cask or ageing began to be a recognised selling point. This will have resulted in a darker colour in the sold product (long before any legal additives – I have no doubt there were lots of other additives) although our earliest references of bottled whisky are often quite pale.

Much blame has, rightly or wrongly, been placed on Macallan’s shoulders for the overt advertising of ‘darker’ whiskies equalling quality and to a lesser extent, age. So successful was this marketing campaign that much of the colour tampering, especially when for single malts, stems from this consumer belief that dark means good.

Possibly out of context here, but did you know that soft drinks are coloured? Fanta, created by the Nazis as a means to compete with Coke – when suddenly unavailable to the Wehrmacht - once released a colourless version of the orange flavoured version. It was a flop – consumers associate flavours with colour and can get themselves to the point where differences are a negative even if the product is as good or superior.

We most certainly take the first bite with our eyes. There is no shame in that. There is also no shame in the whisky industry admitting the crucial part that other symbiotic products have in its success story. A good chunk of the colour and flavours we like in our whisky have nothing to do with the barley being Scottish, the warehouse being dunnage, the sea-coast being nearby, the mashman being third generation or the stills being the same shape they have always been. A generous portion of what we are enjoying in the glass is due to the quality of a different product that seeped into the oak, and survived the journey to the filling floor when whisky (be it new-make or mature) was added.

Time then for maybe a re-think on using Pax? The SWA is all about traditions as I’ve already suggested and Pax has decades if not a century more provenance over, say, the use of ex-Tequila casks. It may be as old or even predate spirit caramel (someone out there will know) which really is nasty stuff. The fact that when it was outlawed Bodegas immediately began substituting Pax for, possibly, inferior solutions just demonstrates that either the policy makers were driven into a knee-jerk decision or had little to no understanding of common practices.

Perhaps the practice was being abused? In which case, distillers could be given the option to use Pax so long as full disclosure was included on the label? Give the consumer a choice – many believe it should be law to state whether E150A has been added.

But Pax, or those of us who love that old-spice, pipe-smoke theme of the ‘60s - ‘80s blends, might be like a pleasant return of an old friend.

FF

-

Dramface is free.

Its fierce independence and community-focused content is funded by that same community. We don’t do ads, sponsorships or paid-for content. If you like what we do you can support us by becoming a Dramface member for the price of a magazine.

However, if you’ve found a particular article valuable, you also have the option to make a direct donation to the writer, here: buy me a dram - you’d make their day. Thank you.

For more on Dramface and our funding read our about page here.