Spotlight: Octomore & Phenols

Four Octomores, their value, and a deep dive into Phenols

Do These Specialty Whiskies Demand a Specialty Price?

With the fairly recent release of the 13 series by Bruichladdich, now’s a timely opportunity to dig into a whisky chased by peathead’s all over the world. Phenols, distillation, value, provenance, and marketing… Better pour a stiff glass now, because it’s about to get real.

So, let’s discuss Bruichladdich and their Octomore series for a spell. We all know the history of the distillery’s revitalisation, their innovation in sourcing unique barley and casks, as well as some of the industry legends that have passed through their halls. But what fascinates me about Bruichladdich more than anything else is provenance. I choose this word carefully, because I want to express quite clearly that I do not mean terroir. Yes, strap in, because I think it’s time to weigh in on the debate.

Terroir has been used in the world of wine for what seems like time immemorial. The idea that a drink can exude such a sense of place that it could only be exactly that wine, from that vintage, from that vineyard, in that soil, picked exactly when it was picked and made in such a way as to express every facet of the fruit’s origin- not left bank bordeaux, rather the right. It’s a beautiful, romantic notion that understandably has helped sell trillions of dollars worth of liquid over the years. An argument can be made for it (although not from me) since wine has principally one intentional ingredient; grapes.

139.6ppm. Okay….

The counter-argument which has always made the most sense to me from a science background is that if terroir is so immutable, then why is it not demonstrable with any significant repeatability in blind tasting? The greatest and most well known example of this failing is The Judgement of Paris. If you’re not familiar, it is well worth reading up on, and there was even a film (Bottle Shock) dedicated to the story. To summarise, in 1976 a number of well regarded French sommeliers were gathered to blind taste French and Californian wines in competition. The general consensus at the time was that France produced the best wines, and that the Californians had no hope. In actuality, the Californians took better marks on average, and this outcome was so controversial that the organiser was banned from a French wine circuit for a year as punishment for his transgressions. Many similar tastings have been conducted over the intervening years, and not once has any solid correlation been made between the wines with “Best terroir” and outcome in judging.

Even if we accept terroir in wine at face value, there are serious differences between wine and whisky. Firstly, whisky is derived from ingredients which do not make themselves readily available for fermentation. Grains must be malted or cooked to break down their starch matrices, and then enzymes either naturally occurring or exogenously added during production must convert those starches into fermentable sugars. The result of this, certainly in malted barley production, is that many of the flavours from the raw ingredient are modified or created outside of the fields in which they’re grown. While there are other process differences between the two, compare single pot still Irish whisky to Scottish single malt to see what I mean here (ie. malted vs unmalted barley). Add to this the processes of distillation, significant maturation and goodness forbid filtration… Can you see where I’m going?

Now all of this is not to say that the means by which a whisky is made doesn’t impact the flavour- obviously. Quite the opposite in fact; my argument is rather that methodology is the driver of flavour in whisky, which after all is much more like its parental beer than it is wine, and brewing is essentially a form of cooking. The chef takes ingredients and then modifies and combines them by process to create the desired dish- whisky is much the same. There are of course intangibles which give the finished product nuance, but the overarching theme of brewing and distilling is how to craft the final product according to one’s desire.

What’s the malt bill? How long should the fermentation be, and at which temperature range? Which yeasts are being employed? What shape is the still? What kind of condenser is used? What are the cut points, and how many distillations? Which cask(s) will the spirit be matured in, and for how long?

This and possibly thousands of other considerations form the basis for a whisky’s provenance. The difference might seem slight, but it’s important.

At this point I think it is worth digressing to a much needed conversation about phenols.

Not all phenols are created equal

We are so very used to mentally surmising phenols as just that thing people mean when some PPM figure gets thrown around. But what are phenols, and how are they different? Well, the actual chemical phenol is a phenyl group (essentially a benzene ring minus a hydrogen) with an attached hydroxyl group. There are also polyphenols which feature more than one phenyl group interlinked, and these form the basis for some important structures relating to casks and maturation (ie tannins) however we’ll leave those for another day, and for now focus on monophenols. Phenol forms the base structure for our other phenols, which may also feature a methyl group (cresols), methoxy groups (guaiacol), vinyl group (ie 4-vinylphenol, which smells medicinal, barnyardy and mousy), ethyl group (ie 4-ethylphenol, similar to 4-VP), or combinations thereof (ie syringol, which is a dimethoxyphenol). In general, guaiacol provides burnt and smoky notes that are discernible only in taste (ie., can’t be smelled) since guaiacol does not readily partition into the vapour phase at room temperature due to intermolecular attractions in ethanol-water mixture observed in whisky. Syringol primarily provides the burnt and smoky notes in smell, although will also contribute to tasting by default through retronasal olfaction. Cresols are generally responsible for characteristics such as coal tar and other natural tar medicinal extractives.

These chemicals all have different volatilities. Volatility is a function of both molecular mass and reactivity- an ethyl group does not have particularly high reactivity, but the extra carbon and hydrogen atoms in the chemical increase its molecular mass, so the volatility is reduced. I’m butchering the true mechanics at play here, but functionally they’re true enough in this context.

These different phenols have similar but distinct aroma and taste properties. Their differing volatility, however, means that a distillery’s production methodology changes their relative distribution- ie cut points and still design. A distillery that has a higher degree of fractionation and reflux, therefore, is predisposed to collect a greater proportion of phenols with a higher volatility. This, I believe, is one of the reasons that Port Charlotte and Octomore have much less of the medicinal character commonly associated with Laphroaig - fewer of the cresols with lower volatility.

Another factor is indeed the provenance of the peat itself. On Islay, aspects of the peat have maritime origin (ie seaweed) and droplets from the ocean are carried in the air to nearby bogs. These contribute to the character of the peat, providing us with halogenated phenols, notably bromophenols (phenol with one or more bromine functional groups) and chlorophenols (phenols with one or more chlorine functional groups). An example of chlorophenols’ aroma is TCP (trichlorophenol, not trichlorophenylmethyliodosalicyl) which has perhaps featured in more tasting notes for Islay whiskies than computers can count. An example for bromophenols is 2,6-dibromophenol which smells like an amalgam of crustaceans, the ocean and iodine. That’s right, the iodine-like smells we find in coastal peated malts are predominantly due to bromine - the old halogen bait and switch! While there are varying trace amounts of iodine in malt whisky, most of the research I could find indicates it to be in amounts below odour thresholds.

Malting & Phenols - Once a By-Product, Now a Deliberate Addition

At any rate, this brings us full circle - Octomore doesn’t use Islay peat. Bairds source their peat for the Octomore series from the Black Isle on the mainland. Although the Black Isle is certainly a peninsula, it is less coastal and unlikely to experience the same degree of sea misting as Islay since it is bounded by the mainland everywhere but the North-East. Regardless, I think the vast majority of us can express some anecdotal experience of Islay vs. mainland peated malts and conclude that there is a fundamental difference. Certainly Scotch Whisky Research Institute researcher Barry Harrison’s work in 2006 and 2007 on peat as a function of geography demonstrated significant differences in peat composition. Harrison also speculated that the geographical and extractive depth of the peat could translate into distinct flavour differences in whisky. Distilleries often specify the location and depth the peat is extracted from, aiming to maintain a consistency in profile according to that distillery’s profile and products. For example, Barry Harrison in 2009 found that:

Islay peat had 50% less syringyl compounds of St. Fergus peat but nearly 100% more than Orkney and Tomintoul peat.

Islay peat had similar guaiacyl compounds to St. Fergus peat but nearly 100% more than Orkney and Tomintoul peat.

Peat extracted near the surface exhibited nearly 50% less syringyl compounds, guaiacyl compounds, and total phenol content compared to peat extracted 1.2 meters below the surface at both the Orkney and Islay locations.

If you are thinking this is a bunch of poppycock, I’ve got one more tidbit to share. In 2010, an expedition was launched to recover three cases of Mackinlay’s Rare Highland Malt Whisky, buried under the Antarctic ice covering Sir Ernest Shackleton’s 1907 expedition base camp. Three bottles were returned to Scotland, showing incredible preservation for their time spent frozen in the tundra. The corks and seals were in incredible shape, with all three bottles showing the same level in the bottle and a 47.2 %ABV. These historical whiskies were subjected to a battery of human sensory trials and chemical analysis. While the sensory trials detected a lightly peated whisky by the panel, the chemical analysis found a 3.5 ppm phenol content in the whisky. Going one step further and leveraging the geographical peat profile research, it was determined that the peat was very likely sourced from Orkney, confirming the historical records that the peat was sourced from the Isle of Eday. Science confirms that at a time where heavily smoky whiskies were the norm, Mackinlay’s was bucking the trend and producing a lighter peated style of whisky in the early 1900s and the chemical analysis could confirm the unique profile of the peat used in the malting process.

Compounding the complication of the matter is the method of peating- the moisture level and temperatures peat is burnt act as variables for the chemical composition of the smoke imparted to the barley. For instance, it was found that the barley malted at Laphroaig was higher in 4-ethylguaiacol than the barley malted at Port Ellen despite using the same peat.

While we’re discussing Bairds maltings, it’s worth mentioning a crucial part of their methodology for creating the absurdly heavily peated malt used for Octomore. To explain this though, we must understand a common misnomer for peated malt; phenols are not absorbed by and retained in malted barley, rather they adsorb to the outer husk. It is this fine distinction that allows Bairds to produce the Octomore malt by re-wetting the grain part way through peating. By increasing the moisture level on the barley husk, the rate of adsorption increases and so more phenols are retained on the grain. The mechanics are tricky here, but essentially the water molecules increase the hydrogen bonding with the hydroxyl and other potentially polar functional groups of the phenols- chemists please feel free to correct me. Baird’s has been reported to burn 8 tons of peat over 5 days to dry a 50 ton batch of malted barley, after which the phenolic content is measured. The moisture content of the peat, the rate it is shovelled on the fire, and the draft through the fire box into the malting floor results in the wildly varying ppm levels we see on the different Octomore releases. The first batch of maltings destined for Octomore arrived at 80.5 ppm.

So we have made it this far without touching on the much lauded ppm numbers. PPM is an abbreviation for parts per million, or a unit of measure that represents the ratio of one thing to all other things in that solid, liquid, or gas. Think of it as a number that describes how many red balls might be in a ball pit containing a total of one million multi-coloured balls. I’ve heard ppm described as phenols per million, parts phenols in a million, and other incorrect descriptions by whisky ‘grammers and podcast hosts. To achieve the concentrations required by the distillery, maltsters often peat a parcel of barley (as described above), measure the phenolic ppm content, then blend the peated barley with unpeated barley on a mass-basis to achieve the desired target phenol concentration for the purchase order.

It is also worth noting that the figures quoted for malt ppm counts are subject to the method of analysis. The easier and quicker industry standard method is a version of colorimetry called Macfalane’s method, which systematically yields a lower total phenol count than the more accurate but costly HPLC. I have been unable to find which method is used for Octomore’s peat.

I think it worth touching on one last point- the ppm on the barley doesn’t necessarily correlate to the PPM of the whisky. Let’s discuss why.

Distillation - The Biggest Impact for Refining the ‘Peatiness’

So now we have discussed what phenols are and how they end up adsorbed onto the malt but distiller’s have the ultimate control over the ‘peatiness’ of their whisky. The process of mashing, fermenting, and distillation can significantly affect the concentration of phenols present in the new make spirit. By definition, distillation is the refining and purifying of a liquid by heating and cooling, thereby any phenols or other compounds that end up in our uisge beatha are intentional byproducts. For vodka producers, they increase the level of purifying during distillation but for whisky producers, these ‘contaminants’ form the basis for future flavours.

Let’s cover some examples here to qualitatively highlight the role of distillation on flavours. Lagavulin and Caol Ila (both Diageo-owned) utilise the same maltsters (Port Ellen, also owned by Diageo) and phenol ppm concentration of the malt prior to distillation yet the whiskies are identifiably different. There are many levers that can be pulled by a distiller when targeting certain flavours.

“Lagavulin ferments for 55 hours, Caol Ila for 80 hours; Caol Ila’s stills are tall and plain, Lagavulin’s are described as “plump”; the stills at Lagavulin are charged to 85-95% capacity, Caol Ila to 50%; Lagavulin takes a wider cut of the spirit run, from 72% ABV down to 59%, Caol Ila collects just from 75% down to 65%.”

Just from the distillation facts above, and excluding the rate of distillation from the discussion, Lagavulin would be a ‘peatier’ and more astringent-type spirit compared to the higher refluxed and narrower-cut Caol Ila spirit, generally agreeing with most of our experiences with these two Islay stalwarts.

Much of this is process specific, and again we can refer to the still design at Bruichladdich being a mitigating factor for the new make ppm count, but it’s worth considering just how much impact the process has on this. The work of Howie & Swan (Compounds Influencing Peatiness in Scotch Malt Whisky Flavour, 1984) concluded that about 80% of phenols are lost in waste streams through new make production with 62.5% lost in the pot ale alone. Of the 20% which remains in the system, the majority are collected in the tails (about 15.7%) to be recycled through future spirit runs with small losses in foreshots and only about 3.4% being collected in the hearts of the spirit run. Whilst this may not be totally exemplary of most Islay distilleries, it gives us context to just how few phenols end up in the new make. Of course the total amount of liquid these phenols are dissolved in as new make is significantly lower compared to the mash volumes, so the new make ppm values are much higher than these percentages might indicate by themselves. Ardbeg, for instance, is quoted with having malt at about 50-55 ppm and a new make with between 17-24 ppm. For reference, Dr. Bill Lumsden is on record as saying these numbers are determined colorimetrically.

Most phenolic compounds have a decomposition temperature well above common distillation temperatures and as such, would not be expected to degrade or be significantly altered during distillation. Accordingly, the impact of cut points, still design, and distillation rate significantly affect the transference of heavier phenolic compounds into the new make spirit. Faster distillation, less reflux, and wide cut points would increase the heavier phenolics in the new make; conversely, slower distillation, increased reflux and a narrower cut point reduce phenolic components. Couple these variables with the ability to somewhat tailor the exact amount and balance of guaiacol, syringol, cresol, and other phenolics based on your peated malted barley’s provenance, and you have a veritable buffet of potential compounds in your new make. Accordingly, I would argue that the actual ppm content plays less of a role relative to the peat’s source and the method of distillation! This brings us full circle back to provenance. Bruichladdich’s utilisation of slow distillation, higher reflux style of still, and mainland sourced peat define this distillery's whisky character and provenance.

To add one more caveat to this long-winded article, we have yet to discuss the impact of maturation. Rather than citing more research, I believe the anecdotal knowledge of the broader whisky-world will work in this instance. How phenols in new make spirits undergo chemical alterations with ageing in oak barrels is still a point of research, however we the drinker commonly observe older expressions showing significantly diminished peat expressiveness compared to younger siblings. So if you want the largest peat experience, a younger whisky will deliver. Ardbeg’s Wee Beastie 5 yo and most Octomore releases highlight the power of youth in the delivery of phenolics.

The Octomore Series

So, let’s discuss Octomore’s provenance. The grain comes from either the mainland or Islay, while the malting is conducted on the mainland at Bairds. Mashing is conducted in a cast iron mash tun; see the argument for potential flavour impact from this in the Signatory Ledaig review. The wash comes from medium-long fermentations, allegedly 60-105 hours, presumably some shorter and some longer although specifics couldn’t be found. It is unknown if the same mashing temperatures, yeast strains, and distillation rates and cut points are used across all of the yearly Octomore releases, making it difficult to side-by-side compare Octomore’s separated by many years of distillation.

Historically, the highest malt phenol content can be found in the Octomore 8.3 release with an eye-popping 309.1 ppm, while the lowest phenol content was 80.5 in the 2012’s 10 year old release.

The Octomore series has unique naming conventions that are not readily apparent on Bruichladdich’s website. Joanne Boyd, Brand Manager for Bruichladdich, provided an excellent synopsis:

.1 series: barley grown on the Scottish mainland & filled into ex-American whisky barrels, serving as the “control” bottle to compare others in the series against.

.2 series: normally similar to the .1 series in phenol content and age, but matured with European cask influences (wine, sauternes, cognac, sherry, or others)

.3 series: barley grown on Octomore Farm, near to the Bruichladdich distillery. Octomore Farm has been supplying barley for the .3 series since 2008.

.4 series: barley grown on the Scottish mainland and commonly uses virgin oak barrels. In some release years, a young virgin oak .4 series is released, while other years feature a 10 year old is released.

Right, enough of all that, we could do with a dram!

Review 1/4

Octomore 7.3, 5YO, 2010 release, 169 ppm. Bourbon barrels and ex-Ribera del Duero red wine casks, 63.0%.

Paid $240AUD. Sold out.

Every now and then we’ll stumble across a gold mine.

The frequency and quality of these finds have ebbed significantly in recent times, but for those that are prepared to put in the work to maintain good relationships with their local independent retailers, some diamonds in the rough will reveal themselves.

One such retailer had five bottles of this release sitting on their shelf late last year- at their original retail price mind you. Apparently some platinum VIP type customer asked to have a case put away for them in 2011 and then never picked them up, so they sat in storage for a decade! When I asked the too-familiar-face (I’m a very regular customer at this retailer) behind the counter if there was a purchase limit, he responded something along the lines of “Not for you old mate”. So in my state of transported glee, I brought over four of them to be rung up- I was tempted to clear the shelves, but thought it better to pass on the find to some other lucky soul. To my delightful surprise, the total came in under what I had calculated- despite the rarity of the bottlings, the clerk had put them through with a staff discount. Making a mental note to buy the gentleman a beer at the earliest opportunity, I took my box of whiskies and high-tailed it straight home to pop a cork right away.

Now, to be fair, two of those four bottles got passed on to whisky friends of mine (at the price I paid, not a cent more) that I knew would also pop their corks at first opportunity. This review is based on that bottle which I first opened nearly a year ago, and which now sits around the two-thirds full mark.

Score: 8/10

Something Special.

TL;DR

Peat vs. dirty & farmy distillate- the winner is the drinker.

Nose

Farmy distillate and highland smoke vie for dominance. Some oddly pleasant isovaleric acid (think stinky blue cheese) plus lanolin, farm mud with sweet dung and sweaty horse blanket up against intense wood smoke a la lapsang souchong, lemon oil, lit thyme, burnt brisket ends, coal tar ointment and a little natural rubber- think heavily peated Benromach and Longrow. The nuances creep out with time in glass; the wine cask is evident with some red berries, a hint of pickled onion and particularly light vinous traces. There’s also just a touch of some floral and bright fleshy fruit notes- think lilac and gooseberries. Ah, be still my beating heart…

Palate

Brutal start- read the nosing notes again, emphasis on the burnt meat, some ash and tar, but have Johann Hegg gutturally scream them from a long ship. We certainly find more evidence of the wine casks here, but in a subtle and integrated sense- the vinous fruit aspects work to augment some of the wilder farmy tones through the medium of intensely phenolic (phenol chemical, singular) smoke. The mid palate to finish unfolds terpenic accents with a blast of lemon oil and moderate herbes de provence, meanwhile the casks have contributed some supporting vanilla and mild demerara sweetness. Retronasal is generally phenolic but with the aromatic florals and white-fleshed fruits back.

Score: 8/10 TK

Review 2/4

Octomore 7.1, 5YO, 2010 release, 208 ppm, Bourbon barrels, 59.5 %ABV. Paid $200AUD in 2020. Sold out.

There’s much less of an inspirational story here- I found this a while back at what seemed a reasonable price having heard the Octomore hype and pulled the trigger, so here we are.

Score: 6/10

Good Stuff.

TL;DR

Smoking blue cheese & pickled fish

Nose

Clearly more distillate driven- dirtier farmyard with the isovaleric notes louder and perhaps even some outright butyric touches too. The youth is more transparent here with a light acetic tone I commonly associate with young peat, plus the barest fishiness- perhaps some pyridines. In a sense the composition here feels a little more like a beefed up Port Charlotte, but otherwise the core DNA is quite similar to the 7.3 - wood smoke, charred meats, citrus oils, some light florals and stone fruits. Deeper investigation finds some light green apple (acetaldehyde) and clearer vanilla, toffee and generally American oak.

Palate

Similar amplification of the farmy isovaleric notes, however the sheer force of the phenolics sets the pace- incredibly savoury smoke almost to the point of an implied burnt bitterness working in the dram’s favour. Funky with more blue cheese and fish tones ducking in and out over citrus, menthol, peripheral acidic stone fruits and more new make-esque acetic ferment (suggestions of Big Mac sauce) and green apple, while the mild oak sweetness helps offset this. Continues with some nice white pepper and soft spices, then the finish and retronasal darts between stinky cheeses, smoked salmon and pure phenol.

As a slight aside, after writing this review I paired what remained in my glass with some aged pecorino, a nice farmhouse pâte and some saison dupont- the experience was significantly improved. That said, there’s very little a nice cheese board and Belgian beer doesn’t help.

Score: 6/10 TK

Review 3/4

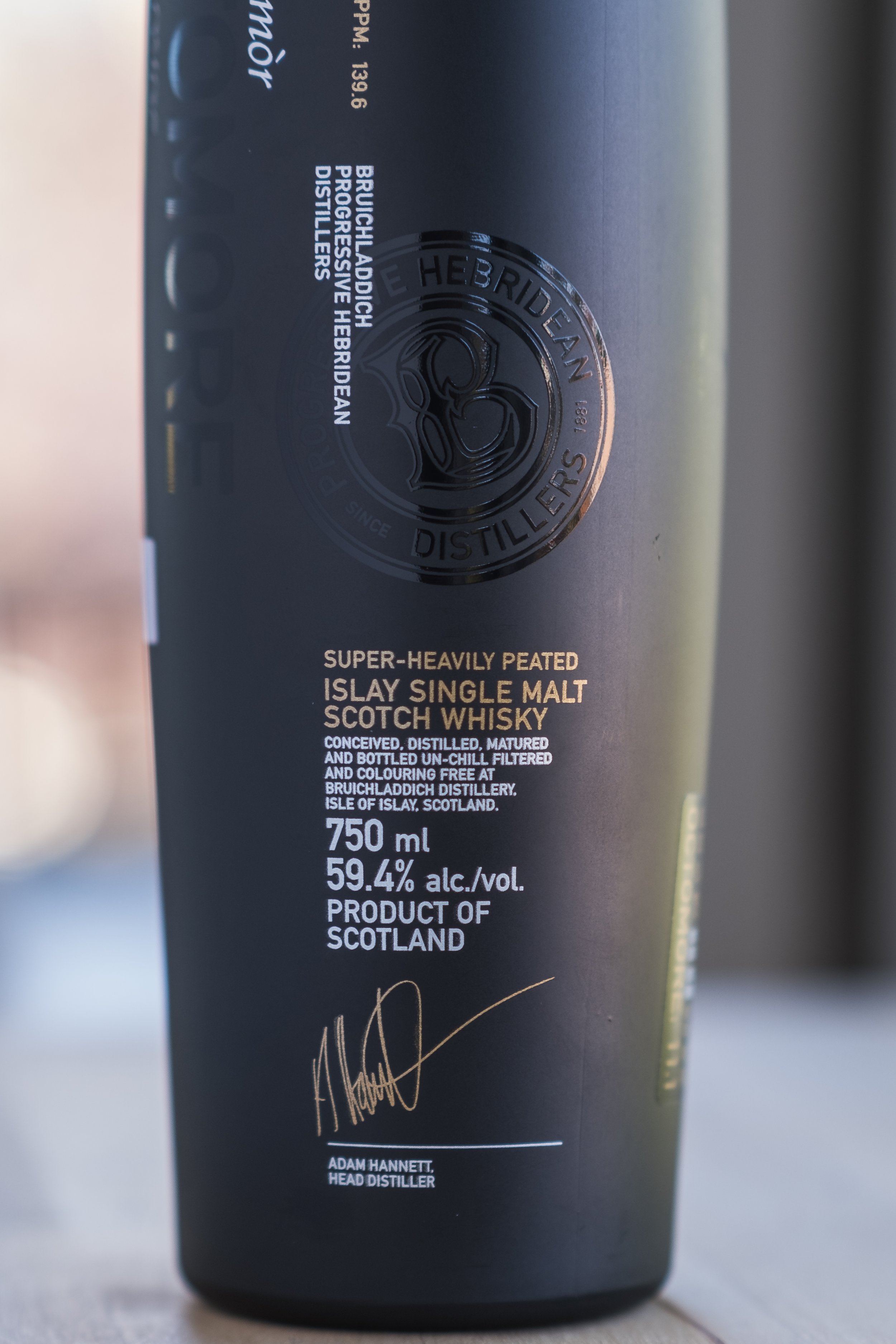

Octomore 11.1, 2020 release, 5 yo, 139.6 ppm, 59.4 %ABV,

$220 CAD (£140)

The mainland Scottish barley here was malted and peated to 139.6 ppm and filled into ex-American whisky barrels for 5 years.

Score: 6/10

Good Stuff.

TL;DR

Port Charlotte 10 yo Turned Up to 11

Nose

Clean, dry peat and a coastal breeze. Confectioners icing sugar. Citrus tang. Background hint of vanilla. Cinnamon powder & mulling spices appear after time in the glass. Crisp and sharp but each note is easily distinguishable from each other. The peat doesn’t smack you in the nose but appears very integrated and restrained, similar to the Port Charlotte 10.

Adding 3 mL of water brings out more peat but it is still quite restrained. The icing sugar sweetness now overrides the citrus, vanilla, and baking spices. After 30 minutes in the glass, the cinnamon and mulling spices present a wonderful counterpoint to the clean peat wafting out of the glass. Personally, straight from the bottle is the way to go but a dash of water would help those with more %ABV sensitive palates without detracting from the experience.

Palate

Clean, dry peat and the pure sweetness of icing sugar continues from the nose. Some maritime and mineral notes immediately follow, accompanied with a tinge of lime juice. As the peat fades, the icing sugar remains on your tongue. The finish lasts quite a long time, surprising for the youth of this whisky and the lack of cling to the sides of the glass. Successive sips refine the surprisingly mild %ABV tingle in your mouth to a cinnamon pastry note.

With a 3 mL dash of water, the same notes are present, just dialled down. It holds up to water quite well, with the finish lasting the same length.

Score: 6/10 BB

Review 4/4

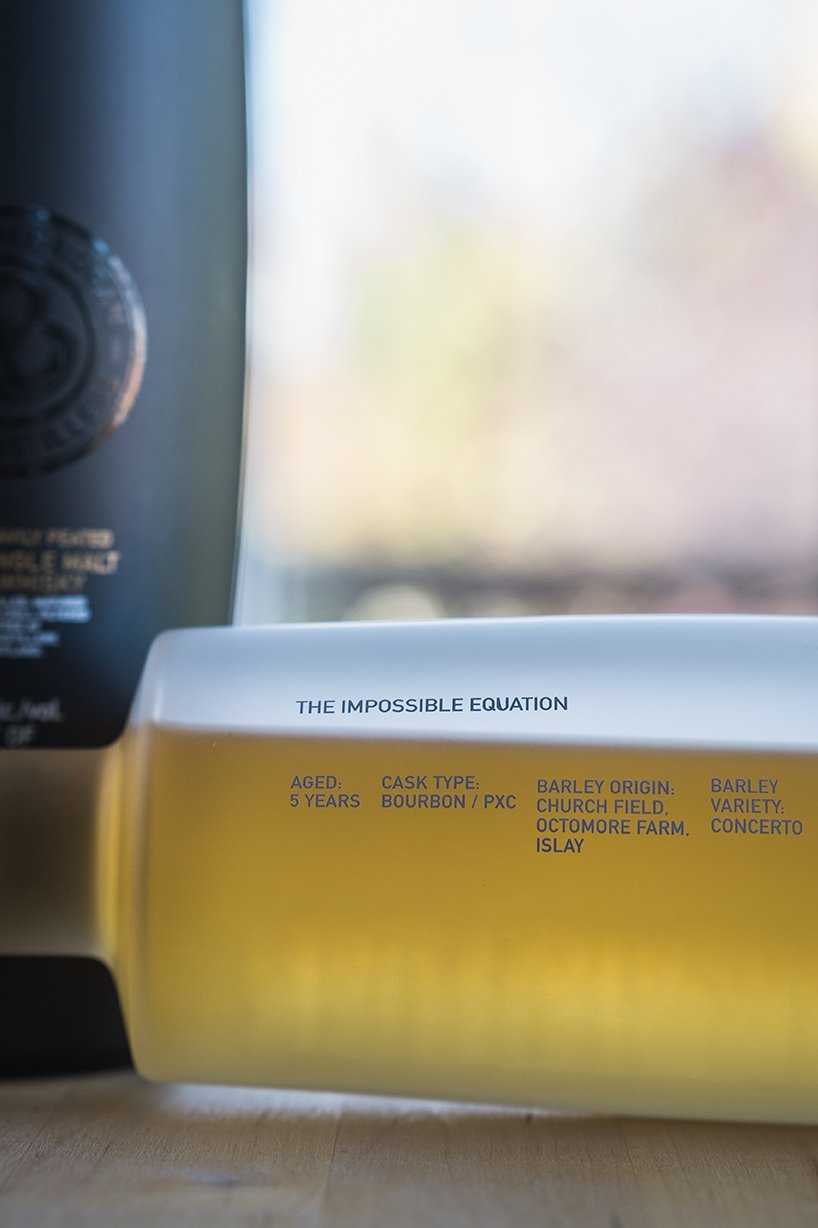

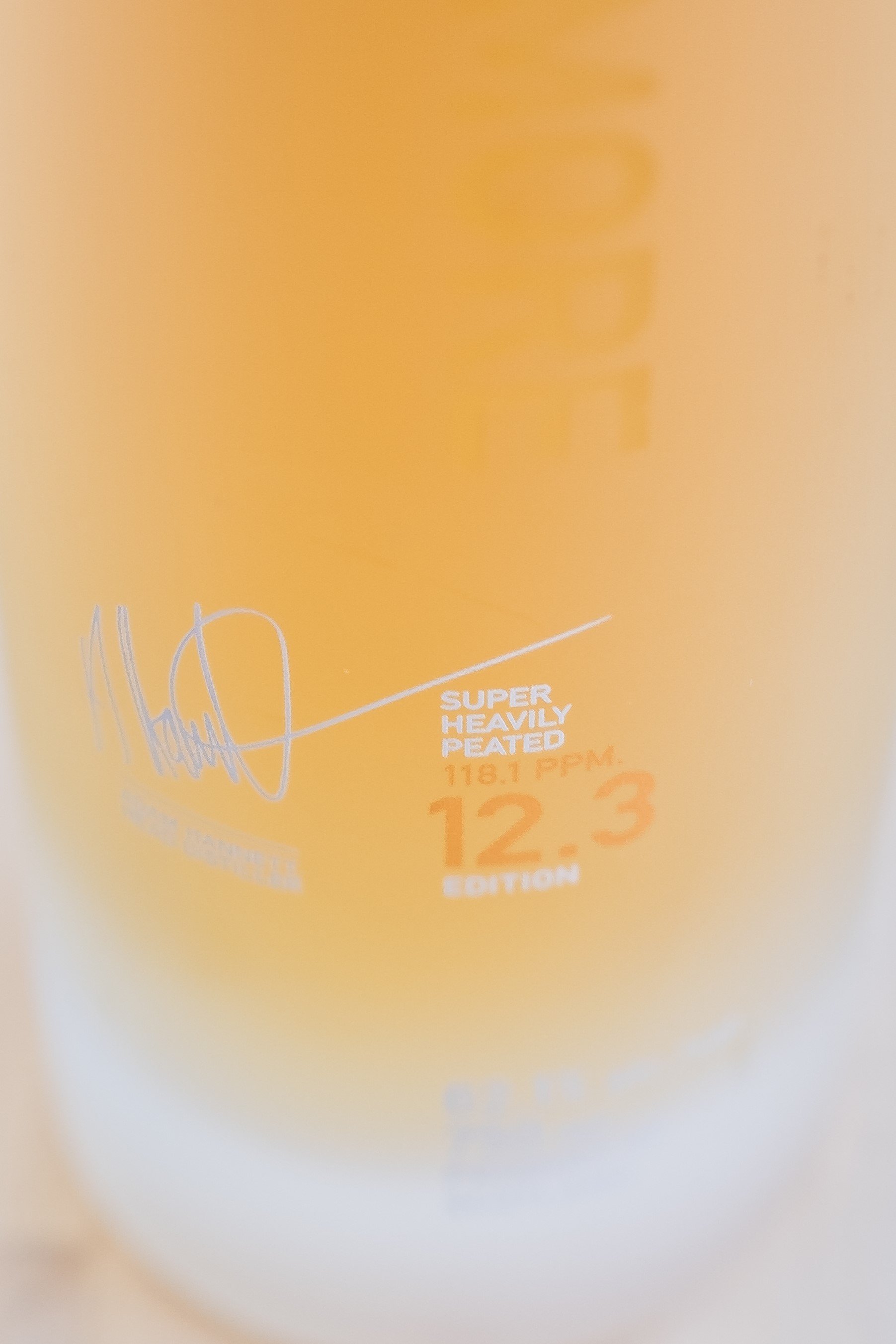

Octomore 12.3, 2021 release, 5 yo, 118.1 ppm, 62.1 %ABV, $315 CAD (£200)

After the Islay-grown Concerto barley from farmer James Brown on the Octomore Farm is malted and peated to 118.1 ppm, 75% of the new make spirit was filled into ex-American whisky barrels, while the remaining 25% spent 5 years in Pedro Ximenez Solera casks from Jerez bodega Fernando de Castilla.

Score: 5/10

Average. In a good way.

TL;DR

A trip to the anaesthetist

Nose

Damp earthy tones. Dark sugars and dates/plums. Hint of the peated Bruichladdich BBQ-style notes found in the 2013 Islay Barley. Hint of a raisin-heavy tobacco pipe smoke.

With 3 mL of water, the damp earthy peat takes backseat to an incredibly sweet toffee and dates, with a hint of maple syrup and tobacco.

Palate

Earthy peat. Dried fruit (cranberry, raisin) and nut bar drizzled with honey. The %ABV tingle is tongue and cheek numbing and more present than the 11.1 release, similar to how szechuan pepper attacks your mouth. Once anaesthetised, the dates and earthy peat notes are present and sustained. The initial honey notes transform to a light toffee. The finish drops off rather quickly despite the clinging viscosity on the glass.

The 3 mL of water helps to tame down the %ABV, reducing the numbing factor considerably. The toffee notes, sherry sweetness, and dried fruits are magnified, now showing as more of a well-balanced sherried peated whisky than before. Personally, the 12.3 release needs a healthy dash of water to increase its enjoyment level.

Score: 5/10 BB

Tyree (7.3)

It’s been a while since I last opened this bottle and had forgotten how intense it is. But more than just being a one dimensional smoke and booze bomb, it has nuance and complexity which all demand attention in an almost overwhelming sense- to paraphrase Deep Purple, everything is louder than everything else. Water helps a bit in the dissection of these elements, but there is something charming about being bludgeoned manically by this at cask strength. This is, in many senses, the type of whisky that flavour chasers might declare a magnum opus in the earlier stages of pursuit. It shrugs off subtlety and balance for the muscle flexing and pose striking attitude that so many attribute with youth. This is not to detract from the quality of what’s in the bottle, just a statement of situational fact. I love this whisky and am glad to have it in the collection, but there’s a reason it is sipped with a degree of rarity. Still being a hopeless peat fanatic at heart, it sits well within my comfort zone. The distillery character and oddly enjoyable wine cask influence manage synergy, so I’m quite comfortable with the score garnered.

Tyree (7.1)

Much like the 7.3 this is intense liquid to the point that my bottle has now lasted nearly three years. I think it says a lot that someone as sceptical of wine casks as me finds the effect taming. Of course cask selection and management plays a huge part in this, but ultimately the spirit demands some wrangling. Please don’t mistake my meaning- I enjoy drinking this in the same way as many other visceral experiences.I would struggle to drink this with much regularity though, if for no other reason than attempting to preserve my olfactories.

Broddy (11.1 & 12.3)

Going back and tasting these after popping them over a year ago, I’m reminded how much I truly enjoy the 11.1 release. It is fantastically balanced, clean, refined, powerful, and lingers beautifully on your tongue long after your last sip - my kind of whisky. It’s a tightrope that is hard to walk and the team at Bruichladdich have walked it well here.

I am surprised that the BBQ-type notes that were detected in the Port Charlotte 2013 Islay Barley were also present in the Octomore 12.3 as they both utilised barley grown on Islay. These characteristics were not readily apparent, to me at least, on the mainland barley Port Charlotte 10 yo and Octomore 11.1. Perhaps these unique BBQ-type notes are coming directly from the Islay barley, or the smell and flavour compounds are formed when the Islay barley spirit is aged in wine and/or fortified wine casks. Interesting observation and something I will have to take note of if I have the opportunity to try another Islay barley-based whisky.

The 12.3 release didn’t live up to my memory of the first few drams. Mulling over this fact while writing this article has led me to recount that on my whisky journey since purchasing the 12.3, I have stumbled across some very good sherried and peated whiskies, primarily from independent bottlers and presented at nearly the same %ABV. Those whisky’s were fractions of the price and provided nearly the exact same experience, and in some cases, eclipsed the nose and palate of the provenance-driven Islay barley 12.3 release. This leads me into the scores.

Personally, given the value proposition, I have subtracted 1 full point from the 11.1 series, and 2 full points from the 12.3. Shocker, I know, and some might think I’m being overly harsh and that I don’t understand peated whisky. In my defence, over a third of my collection is peated, and being in the frozen tundra of Canada, we do rather enjoy a peated dram on a cold wintery day! So for those of you doing mental arithmetic, I arrived at scores of 7 for each of these Octomore’s without considering the pricing, so if you are not sensitive to price, then these are quite good whisky’s in their own unique way! I’m just a single voice swimming in a sea of personal opinions so take my reviews and comments with a blast of cold coastal salty air.

These Octomore’s are good whiskies and something everyone should experience, but not necessarily something that people should buy. Pool your money with some friends to split a bottle, find a local bar that has some Octomore to try, attend a Bruichladdich/Octomore tasting, or try a completely different whisky without chasing the Octomore hype. The 11.1 reminds me of a Benriach Peated Cask Strength (Batch 01) I had with the confectioners sugar and dry peat combo, which is 2.5X cheaper. The Port Charlotte 10 yo, a ubiquitous and mostly available whisky, provides nearly 80% of the experience while being 2.5X cheaper again. The 12.3 follows a very similar trend, with more affordable and similar peat & sherry experience whisky’s in the market. Additionally, the mouth-numbing behaviour of the 12.3 might be off-putting for some drinkers. My mouth goes temporarily into shock every time I pour a splash and it’s something that I rarely experience in my other >60% ABV offerings.

I recommend a “try before you buy” program with Octomore’s, and if they are your cup of tea, then by all means snap it up, crack it open, and enjoy it with your friends. Otherwise, don’t encourage the Instagram post wars, the malt chasing, the auction bottle flipping, or marketing teams by snatching up every new release, encouraging price hikes in future releases to maximise profits. Whisky that sits on shelves doesn’t mean it’s bad whisky, just that the pricing is out of touch with the market. I know I won’t be selling a kidney for a balloted chance at the new Octomore 13 series, coming in at an eye-watering and savings-draining CA$350 (£225) in my area.

TK BB

-

Dramface is free.

Its fierce independence and community-focused content is funded by that same community. We don’t do ads, sponsorships or paid-for content. If you like what we do you can support us by becoming a Dramface member for the price of a magazine.

However, if you’ve found a particular article valuable, you also have the option to make a direct donation to the writer, here: buy me a dram - you’d make their day. Thank you.

For more on Dramface and our funding read our about page here.